By

ROB SIDON

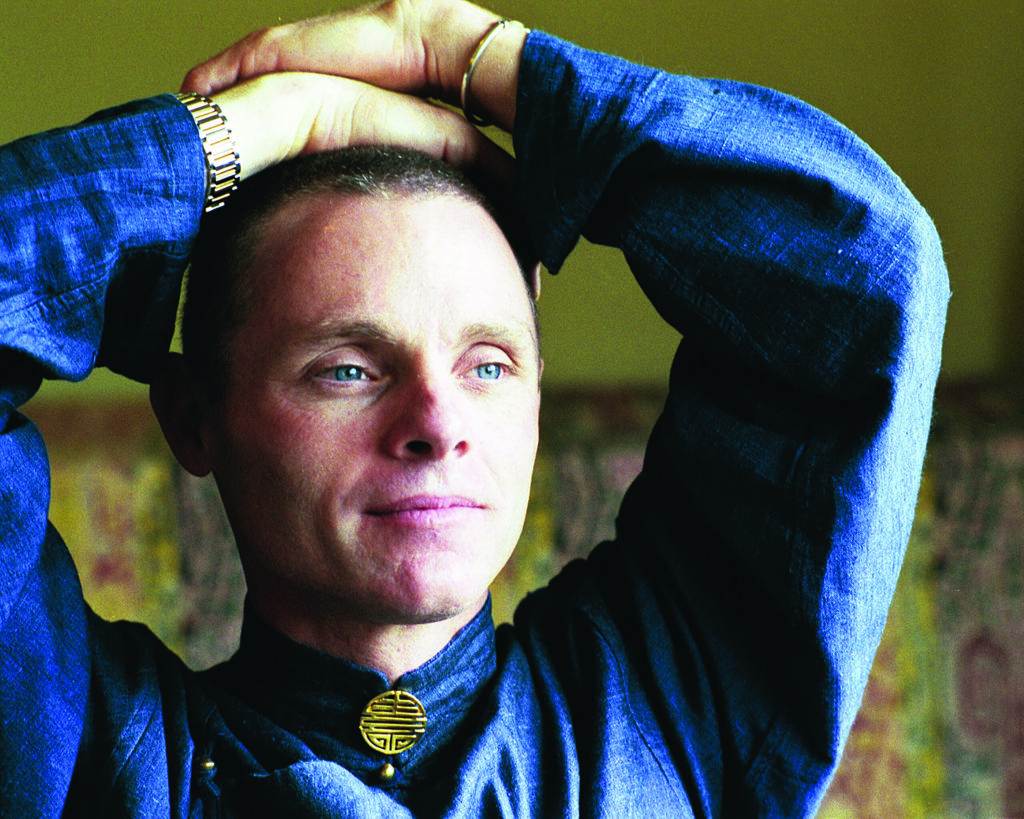

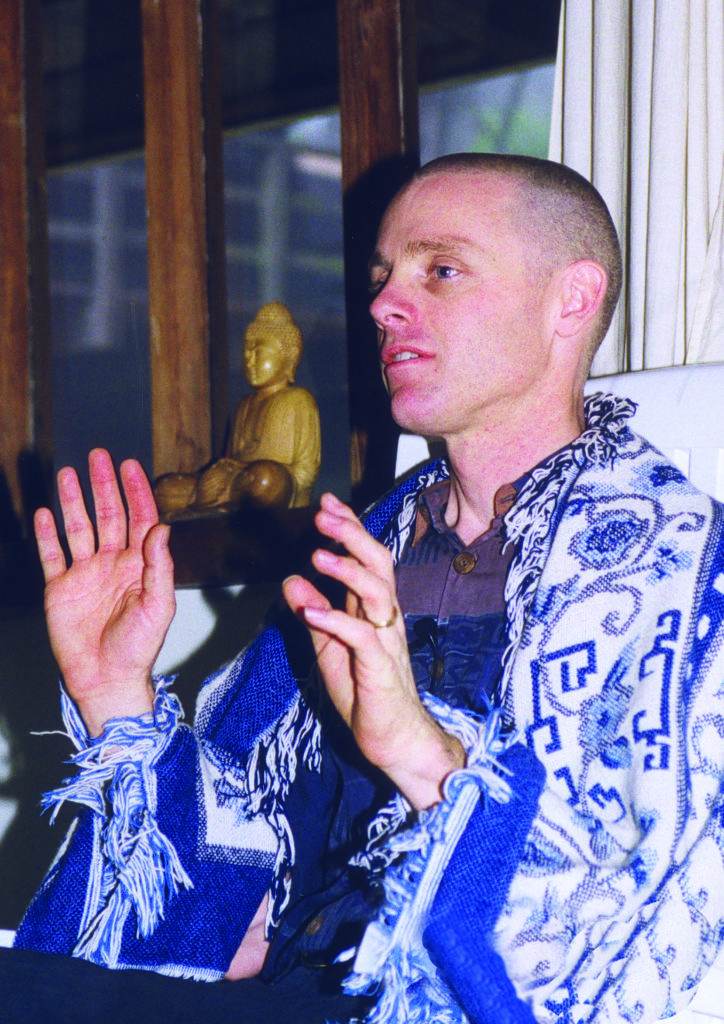

Adyashanti (meaning “primordial peace”), born Steven Gray in 1962, is widely recognized as an enlightened spiritual teacher who grew up simply and happily in Cupertino with his machinist father, his homemaker mother, and his two sisters. A passionate young bicycle racer, he refocused his zeal for competitive training to Zen Buddhist meditation as a 20-yearold after learning about the concept of enlightenment in an Alan Watts book.

He experienced his first lasting opening to unity as a 25-year-old but was deemed unready to teach until his early 30s, whereupon he and his beloved wife, Mukti, founded Open Sangha in 1996. They lead large retreats around the world, where they have earned an impeccable reputation. My candid conversation with Adyashanti took place at his Los Gatos home on the heels of the 2016 presidential election.

Common Ground: You’re part of a rare club of enlightened spiritual teachers. I am not. Traditionally, I would show my respect by bowing or touching your feet or making offerings. What do we do—a high five?

Adyashanti: [Chuckles and high fives] Yeah, a high five is preferable than all the bowing and genuflecting in the world.

What I’m trying to say is that even though we’re hanging out like a couple of dudes, there’s a difference in that you’re enlightened and I’m not. What’s the difference?

[Chuckles] Is that the beginning question? What’s the difference? The most direct way of saying it is, I know there’s absolutely no difference between us. You might imagine there is, but if enlightenment is anything that’s authentic, that’s what it is—knowing there isn’t difference. Obviously, our personal history is. The way we look, our personalities—there’s lots of relative difference between you and me, but on an essential level there really isn’t any difference. Enlightenment, or whatever people want to call it, is simply seeing things the way they are. Once you get through all the fancy talk, whether it’s talked about as bliss or peace or all this [points around the room], it’s seeing the sameness within diversity.

Easy for you to say since you’re in the club, not me.

Whether it’s rare or not is neither here nor there. If anybody thought that enlightenment meant they entered into a special club, that would be a good indication of its inauthenticity rather than its authenticity. I understand what you’re saying, and I remember having that point of view. It’s part of what you lose with all this—those viewpoints that keep separating us.

Can you share about your trajectory? You grew up around here, right?

In Cupertino in a very normal, loving, middle-class family. My dad was a machinist; my mom was a homemaker. I grew up a happy kid—now that may be rare! My parents somehow got that across to me—that absolute unconditional love. I had two sisters and grew up with aunts and uncles and grandparents living within a half an hour. I don’t mean to idealize my family because we had ups and downs, but for the most part we really got along with each other in a supportive environment.

Was there a religious tradition?

Protestant, but the whole church thing stopped as fast as it began. Both my parents were quite religious but not really churchgoers. They probably felt they were supposed to haul us off to church and Sunday school, where I remember being in the kids’ room coloring pictures of Jesus in a cartoon book and thinking, “This is totally ridiculous.” Fortunately, they didn’t force me to go. One of my grandfathers was a deacon at the church and often, when the relatives would get together, a free-ranging discussion about religion and spirituality would pop up. Even as a 7- or 8-year-old I was inexplicably drawn to that conversation.

Didn’t you have an early recognition about adults—that they are crazies who actually believe their thoughts?

I was a great eavesdropper. Kids have the ability to understand more than their parents ever imagined. So I could listen to a given conversation and notice when one person would even mildly start to manipulate the other—to get a little strategic advantage. It didn’t add up to me. I would think, “This is strange, why do they do this?” One day I got a very simple insight into the adult world [chuckles]—they’re crazy. It sounds like a negative judgment from a kid, but I didn’t experience it in a negative way. I wasn’t frightened. I experienced it as nothing but positive and calming because I just wanted to understand: why does this happen? What I saw was that adults are prone to getting lost in their thinking and their impulses. Adults will manipulate a conversation but not even know when it’s happening. They are very prone to getting lost in some weird communicative world of impulses. In my little kid mind it condensed into one phrase “Oh, they’re crazy.” It was a nice relief to understand that, and it put the whole thing to rest.

How different was your mind as a 7-yearold versus now?

When I grew into my teens [chuckles] I started to do the exact same things. I lost some of the clarity, although never became completely engulfed.

You always maintained a witness state?

I guess in spirituality it would be called that. At about 16 I started having typical teenager thoughts like, “My parents are stupid; they don’t understand anything,” but I was so aware of it. One day I walked out of breakfast and said to my mom, “I just want you to know that I think you’re really stupid today. But don’t take it personally because I know it’s just this rebellious teenager thing that I’m going through.” So I had awareness of it.

Were you good in school?

No. I was born with dyslexia and had trouble with reading and arithmetic. I was up to normal speed in reading by third or fourth grade, but in mathematics I probably never caught up. All through junior high school when math time came, little Stevie would walk out of a class full of kids to join the little special ed class. It would have been the perfect setup, but I don’t ever remember having shame.

Did you have any inclination you’d become a seeker?

I would call them “having one of those days.” I’d wake up in the morning and the whole world would look different—I’d see everything as one. As if a perceptual shift happened in the middle of the night, and I’d wake up and I’d immediately know to say to myself, “Okay, it’s one of those days.” This continued from childhood through college. As I got older I would have to make a conscious effort not to look at people too closely because when I was in that state, I would tend to look at people really closely. I was seeing something I couldn’t name. It was as if life was looking back at me. I had to discipline myself because even from a distance people could feel my doing that.

Here comes the extraterrestrial. . . .[Chuckles]

Yeah, I guess so! [Laughs] Also, when I was a little kid I frequently saw this big white light at the end of my bed at night. It would just hang out there. This was just part of my life and didn’t totally stand out. For all I knew this is what everybody else experienced.

You were a competitive cyclist. What was the effect of that discipline, particularly as you started getting into Zen Buddhism?

I was consumed with being a high-level competitive cyclist through high school, riding 300 or 400 miles a week. That was my life, especially when I got a feeling for what my potential might be—at which point it became an obsession. When inspired, it was a discipline but a discipline that didn’t feel imposed. When I was a kid, if something captured my imagination like skateboarding or unicycling—the list goes on and on—then I was like a light switch. It’s 100% on or 100% off.

At around 20 I read a book by Alan Watts, and I literally read the word enlightenment. I had no idea what the heck the word did, but it was like a nuclear explosion went off inside my body. It was the oddest thing I had ever experienced. I knew with absolute certainty that my entire life was reoriented. I had no choice in the matter. So discipline came in handy when I started practicing Zen.

The competitive type-A athlete would become an aggressive meditator?

It was the beginning, like kicking a rock off the top of a mountain. I could feel the momentum building. I started experimenting with a little meditation, and then it became its own obsession. I found a teacher who lived in Las Gatos and taught in her living room. Her name is Arvis [Justi] and was a lay teacher who was asked to teach by her teacher, Taizan Maezumi. She’s close to 100 years old now. We talk. She holds the dearest place in my heart. Yes, I was an aggressive meditator with overwhelming drive—like a dog with a bone who just wants to chew it up! [Laughs] I drove myself harder than any of my teachers ever recommended. I built a meditation hut in the back of my parents’ backyard and would get up around 4:00–4:30 in the mornings and alternate periods of sitting and walking until midnight. But unlike in sports, in spirituality I never felt competitive with other people.

That’s extraordinary, but at some point you have to let go, right?

Yes, it sounds rather impressive but the flip side is that I was striving too much and was too tight. You can only keep that up for so long. I remember thinking, “Is today when I completely lose it and psychologically crack and end up in some institution?” Fortunately, the letting go happened rather than the crack up.

Then something happened, but it wasn’t by your doing, right? What happened?

It was a little bit of both. It just happened one day when I was reading, and all the intensity of those years just came to a crescendo very quickly and something cracked. I just realized, “I can’t do this.” Those words—“I can’t do this”—set off another version of a bomb exploding, and a powerful Kundalini thing occurred that I was certain was going to kill me.

The bomb effect—could you further describe it?

It was a reflection of how strong my willfulness was. I tried to let go before but there’s no way. It was like an instant energetic explosion inside of me. I was breathing as if I was running the 100-yard dash. As an athlete I trained to know I was past my max heart rate and that it couldn’t beat like that indefinitely. It was energetic chaos and I realized this is going to kill me. For some reason this strange response came up from my guts—instead of from my head—that said, “OK, if that’s what it’s going to take to find out what this is, then let’s do it today. Right here, right now!” Recounting it now I can still feel the intensity of it. I was literally willing to die, to just physically expire. It wasn’t courage. I had discovered something that was deeper than the survival instinct. As soon as I said that, like snapping my fingers the whole thing just went boom, and I was in a different dimension. There was no energy at all—no body, no mind. There was absolutely nothing. Total nothing.

Then there was just the experience from there—of insights happening—almost like hundreds per second. They were happening so fast that I couldn’t register anywhere near all of them, but I could feel they were being downloaded into me almost like you would download a program into a computer at an extraordinary rate. It went on for I don’t know how long and then I just opened my eyes and everything was peaceful and calm. My respiration was calm.

At a certain point I just thought this seems to very ordinary, so I did what I usually do: I got up and turned around and bowed to my little Buddha statue in the corner. Somewhere in the middle of that bow, by the time I lifted my head back up, I was in hysterical laughter. What I saw in looking at that little Buddha figure was the representation of everything that I was seeking. I just thought, “I’ve chased you for years. I’ve driven myself crazy for this—only to find out that I am what I was seeking.”

Now that sounds cliché in today’s spiritual world where you hear this like a dime a dozen on the Internet, but I’d never even heard that. The whole thing seemed so ridiculously funny. It seemed like I had been the butt of this incredible joke. I just started laughing and laughing—just an incredible relief. It seemed like, “God, you’re a good comedian and it’s really just comedy.” All the ludicrous ridiculousness came bubbling up. That was sort of my first opening at 25.

So this was the turning point.

That was the beginning of the turning point. From that point the seeking just didn’t make sense anymore because why would I grasp for something that I am? Interestingly, for five or six or seven years prior I’d had a foretelling that I was going to physically die at 25. For some reason I was never concerned about it—but it really was a death experience.

The angst fell away?

All the angst fell away.

What about that chattering mind?

No, it didn’t, but it was much quieter. I knew from what I had experienced that the chattering mind had always been happening completely on its own. I stopped seeing it as problematic. I realized that all those years of thinking that I needed to stop thinking only got me more obsessed with thinking.

So life goes on, but you’re not yet teaching, right?

No, no, no. I wasn’t ready to teach. Fortunately my teacher had the good sense to see that. Actually, I didn’t even tell her. I didn’t tell anybody. It felt so sufficient in and of itself. Months later I thought, “Wow, I should tell her; it might be nice for her to know.” So I told her what happened and she just said simply, “Very good.” That was it. She didn’t make a big deal of it, nor have a celebration. She didn’t pat me on the back and say, “Welcome to the club.”

Your stateless state didn’t dissipate?

The knowing never left me. I couldn’t have stayed in the state when I was having the downloads and no sense of a body. But the knowing, which is the important thing—not just the intellectual knowing but the knowing through experience—that never left. As I was leaving the tent that day I remember this little voice came in. It was a voice I had learned to trust that said, “This isn’t all of it. Keep going.” I remember thinking, “Damn! Don’t I even get a couple minutes to think I’ve completely and utterly arrived?” But I knew it was true. I was like, “OK, what I’ve seen is real and true—and I haven’t seen the whole of it.” So I kept doing everything like I did before, but it was more of a curious exploration. But you know, the odd thing was being 25 years old and having no fear at all. I knew I had had this definitive experience, that what I really was could never be harmed. My body could be torn asunder, but something very essential about me could never be harmed. It was an interesting time over the next five years as I adjusted to what that was like. That could lead to great clarity and also great stupidity.

It could lead to insanity.

It could. If you took it all very personally.

Recently, I’ve been affected by a young man I knew who ended his own life. Arguably, he might have opened the portal too wide too soon. The point is, we think we want something on the other side, but the passage can be scary, no?

That can happen; people can go into psychosis. When you take away all the spiritual niceties, yes, it can be scary. There’s the existential fear of the void, the fear of annihilation. It’s one of the most common questions I get. I’ve seen people force themselves through, and if they’re vulnerable or psychologically wounded or divided, it can be really challenging. I like to just give it to people straight: What it comes down to is, “How much do you want it?” I often say, “It doesn’t have to be a head-on confrontation. Do what’s wise. You can slow it down and take it in little bits.”

You never looked back?

No, never. But I often say, “Don’t use me as the quintessential example.” There’s a lot of oddities about the way I was hooked up. I could have really wild experiences and different atypical states of consciousness, and yet there was a sense of normalcy about it even though it was very un-normal. None of it really pushed me that much off center. I never went to my teacher and said, “I don’t know how I’m going to live this.” Like most things in life you learn by trial and error.

It seems humility is the gateway. Didn’t you have an experience of seeing your past lives like a selection of movies?

That was another opening to unity—very clearly in my early 30s.

Can you talk about that experience?

Gosh, I wish I had better language to say it instead of cliché spiritual lingo, but at that time I was having prolonged experiences of no separation. It was like, “Oh my god, I am appearing as a tree, or a pot, or a couch, or every inanimate object. I’ll be darned. How odd is that?” There was no sense of otherness and only oneness. Not only was there oneness with pleasant objects but with the whole cosmos and everything in it—the good and the bad, the pleasant and the unpleasant. That everything and everyone is the Buddha, the Christ, with no exceptions when seen through the eyes of God. This was—and still is—a profound opening to unity. But a few weeks after that is when I had all these—what people call past life experiences. Whether they were actually past lives is unimportant to me, but I got a peek into some other existence. Each was centered around a very specific event where usually there was some unresolved confusion.

As an example, in one of them I was a fisherman off the coast of Ireland and a big storm knocked me overboard, where my head was hit rather hard and I am on the outside seeing myself sinking and drowning.

Are you wearing the garb of the era?

Yeah. I’m wearing the garb of the era. It wasn’t like modern times. And I’m sinking toward the ocean floor sensing the confusion like, “What in the hell just happened? Where am I?” When you look at it from the outside like looking at a movie I thought, “This poor guy needs to know what happened.” I just knew intuitively I need to bring clarity and remove confusion. So in my own being I just talked to this guy, saying, “Hey, there was a storm. Do you remember that storm? You got hit on the head, it knocked you over, and you’re sinking and you’re going to die—and everything’s perfectly okay.” Then I could see the image of both him and me with the confusion dispelled and then letting go. Then that movie would disappear. There was resolution in both past and present time, and then a little while later another movie would show up.

What’s another one?

Being a very desperate and confused sadhu [spiritual mendicant] on the side of some river in India totally beside myself with grief. I don’t know his whole history, only what was felt in that scene—that I had been a sadhu, seeking for some years and for some reason I ended up in this place of utter desperation.

Was there a death?

No. It was questionable what that guy might’ve done had I just let it go on. Maybe he would’ve walked out into the river and ended it all. There was a feeling that might have happened, but again, as the onlooker I casually slipped in and said, “Kid, everything’s okay. You’re all riled up about nothing. You aren’t what you’re thinking. You may not see it now but don’t worry, you can’t avoid the truth of yourself indefinitely. So just relax a bit.” And then again there was a feeling of relaxation and resolution. Then that scene faded away. It went on like this for a few weeks.

Wow, you’re just getting the whole download.

Not continuously, but when I’d sit to meditate I’d often have these downloads show up. Were they actually past lives being resolved? It absolutely felt that way. I’m not prone to magical thinking—I’m rather on the other end of that scale. But I did have the experience that those lives were being created in the present moment. That the present moment was creating the entirety of the experience of the past.

I’ve tried to wrap my head around that—that there is no time. That everything is happening now. Like I lived 5,000 years ago and 5,000 years from now, but it’s all now.

[Both laughing] You have my sympathies. We’re in the same boat, my friend. We really are. I can’t get it intellectually either. I can’t explain it. I don’t think the intellect can do that. Maybe if you’re some particle physicist you can wrap your head around it with equations, but I can’t say even if it’s true. I suppose I don’t need to know.

I feel relieved that I am not alone on that one. Getting back to our timeline—so you had these openings and then came the dharma to become a spiritual teacher?

Apparently. I did become a spiritual teacher. Little did I know. I envisioned something like my teacher had, with 10 or 12 people in my living room. I had no idea it was coming—fortunately. I wouldn’t have wanted to know.

I imagine it’s frustrating to explain the unexplainable to students. Do many people actually get it? Do you like teaching?

A whole lot more get it than I imagined when I started. I ended up being wrong in those regards.

I do like teaching. It has its challenges. I’m basically an introvert, though people wouldn’t think this by seeing me onstage. So it’s a little bizarre, the whole aura that you’re full-on perceived through the eyes of that projection—as a spiritual teacher. That took a while to get used to. I’m a fairly ordinary blue-collar guy, so I get less overt projections nor do I seek them. Basically, I feel extraordinarily lucky to be doing what I’m doing. I call myself a one-trick pony because this is the one thing that I’m good at outside of just physically pounding myself into a pulp in some endurance port.

Aren’t you scared?

Of what?

The perilous pitfalls of being a teacher.

Oh sure. One of the first things my teacher said to me right after asking me to start doing this—she said, “If you ever feel like you might succumb to some of the temptations of being a teacher, get out before you hurt someone.” That’s been my personal commitment to her. That’s my devotion and what keeps my feet on the ground. I remember that day and I told my mom, “You’re the person who changed my diapers and I came out of you and I can’t bullshit you, so I’m entrusting you, Mom, to just keep an eye on me. If you ever see me going off the beam I want you to tell me.” And I told my wife, Mukti, the same thing. It’s a bit of a minefield, and you really have to keep your wits about you. It’s a good idea to have people watching out for you.

I gotta hand it to you. I’ve been tracking you for a long time thinking, “OK, a young guy spiritual teacher. Eh, let’s see what happens.” But you have an impeccable reputation.

That’s nice to hear.

The path is littered with fallen teachers who succumb to sexual desires and reach into the till.

I’m lucky because way before I was a teacher, I’d never had that thing in me that wants to control or manipulate people. I encourage people by saying, “This is your thing. Don’t make this about me. If you do, it’s at your own peril. You’re the authority of your own experience, not me.” I never liked exercising power over people, so that comes in handy for doing this. Also, I feel lucky because I think I was born with the monogamy bone—it’s just how I’m made. It doesn’t mean that I don’t have sexuality or can’t notice an attractive person. It’s not even a moral or ethical thing. It’s just the way I’ve been from day one. So that too comes in handy. I can’t even take credit for it.

Do you feel like you walk the razor’s edge? Do you fear a fall from grace because of temptation?

In the early days when the first teachers came from India and the Orient—these were mostly guys coming out of situations where historically the way they dealt with sexuality and money was by not dealing with it. They became celibate and lived in cloistered environments. As long as they were under that protected culture, then it may work, but by coming to the United States—whammo! They’re feeling all these powerful impulses and drives that had been contained. It’s easy to assume they were all charlatans lacking in integrity to begin with, but my sense is that many just started experiencing things you only experience when you’re exposed to the way life is. It didn’t work particularly well in the Catholic church either. There is a myth that spiritual insight and psychological maturity always come together, but they often don’t.

Do you observe spiritual ambition in students?

There is a lot of spiritual ambition. I meet people all the time who have a little breakthrough, and the first thing they do is want me to ask them to teach. They’re often disappointed and/or upset with me when I suggest that they just got their foot in the door and I think there’s a hidden ambition that can be a really dangerous thing.

Why do you do it? Why do you even bother talking to me? [Laughs]

That’s a great question. This sounds overly simplistic, but one reason is because I was asked to by someone that I profoundly respect. I would never dream of doing this without being asked. The other part is more nuanced. When I first started, in the first three or four years, there was a certain amount of zeal and energy and intensity to it. I couldn’t imagine it being any other way. Then slowly that started to dissipate. I used to feel like a young dog panting for a walk, and now I feel like that old dog on the porch that just doesn’t get ruffled about much. The missionary zeal disappeared long ago. To answer the question honestly, it’s not because I’m such a compassionate guy who wants to help save all beings. It just feels like this is my dance. Everybody has their dance in life and this happens to be mine, so I do it as well as I can.

What does ruffle you?

My computer, an inanimate technological device that frequently doesn’t respond the way I want, and I don’t always have the skill to fix it. Admittedly, that’s a very trivial thing to bring up.

And ironic, given that you were born in and raised and never left Silicon Valley.

[Laughs] Ironic place for a dyslexic who has a hard time with math and who has basically had no memory his whole life.

I am told you suffer with ongoing extreme pain. That must not be fun.

No, it’s not fun at all. A kidney infection left me with severely painful nerve damage. I’ve pretty much been through the ringer.

What’s the effect on you, spiritually speaking? Like doing penance?

It’s interesting you say that because the severe level of pain can be humbling to the point where getting through the next day is unimaginable, and I can only think about getting through the next 30 minutes. I can’t romanticize it at all. I can’t even say it’s part of the path. It’s part of my life, and it definitely keeps my feet on the ground and has made me compassionate for whatever other people are experiencing.

I didn’t even speak about this for many years because I didn’t want to be the focus of attention but then thought, “Hell, anything a spiritual teacher can do to humanize themselves in the eyes of others is a good thing.” I did get some letters and emails saying, “I thought you were enlightened, and now I see that you’re prone to illness and pain. I’ve changed my mind and I have to move on.” So [chuckles] it’s nice that I could be a part of knocking that projection out. You don’t get a special status in life just because you’ve had some realization. If you think so, just wait awhile—something will come along.

Talking about penance, I wonder if you considered the path of the renunciant versus that of the married householder?

No, I would’ve made a terrible monk. I’ve always been quite independent and uncontained by nature, which would be frowned upon in most spiritual communities. I would’ve driven them—or myself—crazy.

For those on the householder path, it’s the relationships that prove to be the great challenge and the test. Is that your experience?

Mukti and I met when I was 33, about a half year before my teacher asked me to teach, and we married. I certainly had my own stupidities in relationships before meeting her, and I hesitate because I don’t want to create another image, but I discovered something being with Mukti that I would never have imagined in my wildest dreams. I don’t even have word for it. It is the most amazing thing in my entire life. That’s what it is. I owe a tremendous amount to her. She is the object of my secret devotion. She is where I see God the clearest.

What effect does she have on you?

I’m not putting a projective mantle of perfection on her, but she exhibits almost all of the natural qualities they try to enhance in Zen training—incredible attention to detail, patience, kindness, and selflessness. So just to live with somebody like that, I’ve absorbed a tremendous amount by osmosis. By birth she has a bhakti [devotional] nature and is very relationship oriented. She was a spiritual seeker since she was a kid too, but to see how powerful that determination for enlightenment was in her taught me—like wow, it can take any form. A sincere desire to connect and meet her husband at the deepest level without any jealousy. She’s teaching in her own right and has for quite a while.

It’s not the submissive feminine thing?

There’s no secondary role taking place. She’s more independent than that. I wouldn’t be attracted to it. In the teaching aspect we’re absolutely peers. Good Lord, how could we be together otherwise? I rarely play a teacher role to her and almost only when she specifically asks for it.

Didn’t you have a similar relationship with your father?

He was a machinist, and in my early years of teaching I was working full-time in his machine shop. He was my father and my boss. He didn’t come to see anything I did for two years, and then he heard a little tape and [snaps fingers] he was on fire and literally came to every single thing I did. At the retreats I was his teacher. This role changing was happening but very simply and naturally.

Your mother is still alive, but your father died recently. What was the effect on you?

We were always extremely close. We probably spent more quality time together than most sons do with their father in three lifetimes. He had a heart attack and then a year later a stroke. That went on for about three years until they found out he had advanced cancer and only lived another couple of months. It came slowly. I felt honored to usher him out of the world in the same way he ushered me in. I remember right after he passed, I washed his body. It felt like the proper and respectful thing to do. But to be totally honest I just experienced a blip of grief. My sense of it is we had no unfinished business. It’s always easier to let go of somebody with that preparation.

Hypothetically, had Mukti been the one to pass, could you envision the same dispassion or minimal grief?

You never know, but had it been Mukti that died, I imagine I would be devastated for quite some time. That’s just an honest guess. Life does have an unavoidable tragic aspect to it. After all, we still have a very human aspect to our being.

Speaking of tragedy, our so-called Bay Area conscious community is collectively mourning the election.

Ah yes! [Laughs] We want to put it off on other people, but it’s just a big blown-up version of us. We’re getting a good look at ourselves in the mirror, and for a lot of people it’s not comfortable. So we do what human beings do: make enemies where each side is angry, upset, and obsessed with its own point of view. I’m a history buff, and I did watch with great interest but with increasing disgust. Trump holds up the mirror of our country’s racism, bigotry, sexism, and whatever is amassed that has been peeled away. I’ll wait till I see what his actions are. If his actions are terrible, I might be the first one out there protesting. I’ll make my decision based on action rather than rhetoric, but it’s clear that civility is a quickly diminishing part of our culture. I hope there may be a wakeup call of “Look how we’re treating each other. This is undignified.”

Some would say Obama had dignity.

I think he did. As things often go we went to the equal and opposite—both personally and collectively. Very rarely does one swing to the center; it’s usually more chaotic than that.

Any final message?

Oh my gosh, are you kidding? [Laughs] I didn’t have a message to begin with. No argument with the world, others—or God.

Rob Sidon is publisher and editor in chief of Common Ground.