How Back-to-the-Landers, Longhairs, and Revolutionaries Changed the Way We Eat.

Jonathan Kauffman was born in 1971 and grew up in a Mennonite family in rural Indiana. His parents were deeply influenced by Francis Moore Lappé’s Diet for a Small Planet and the recipes from More-With-Less, which led to an ecologically mindful diet that included plenty in the way of brown rice, muesli, yogurt, sprouts, lentil casseroles, and tofu stirfries—the same counterculture fare that would become the subject of his popular new book.

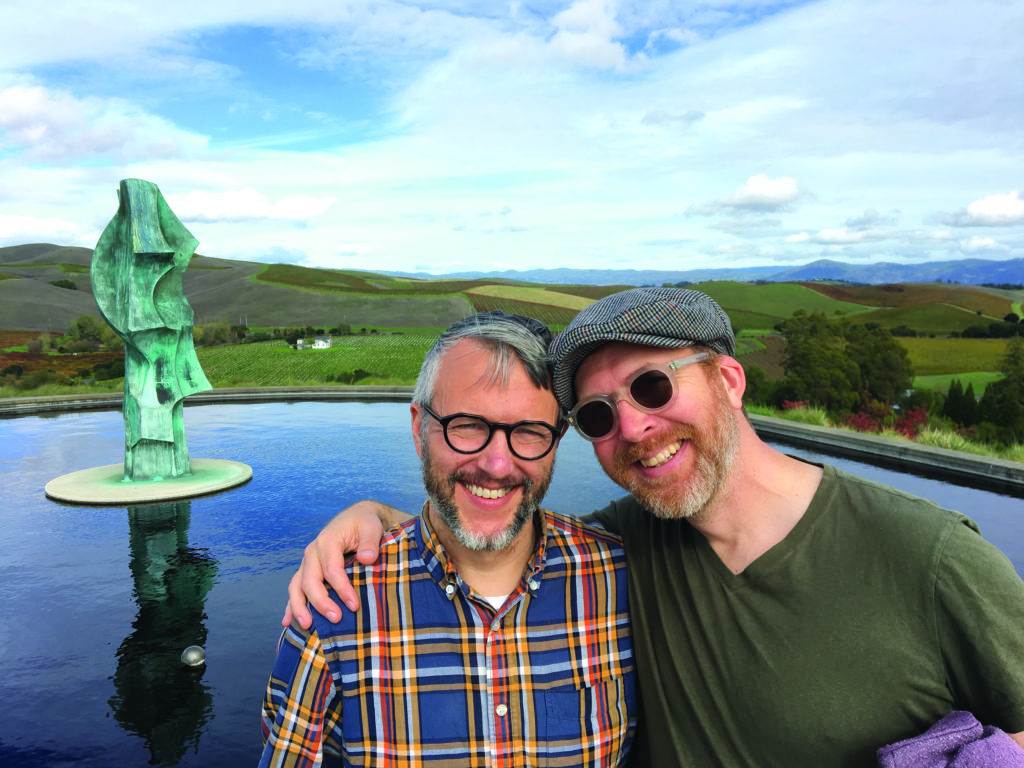

Jonathan attended Macalester College, where he studied comparative religions and developed a fondness for Soto Zen philosophy. Working college restaurant jobs, he took a liking to cooking before moving to San Francisco in 1993 and becoming a food writer, first with the East Bay Express and now with the San Francisco Chronicle, where he covers the intersection of food and culture. Along the way he left the Mennonite church, married his vegetarian husband, and adopted a daily zazen meditation practice associated with the San Francisco Zen Center.

Jonathan’s writing has won awards from the James Beard Foundation, the California Newspaper Publishers Association, the International Association of Culinary Professionals, and the Association of Food Journalists. We caught up with him to learn about his journey to the 1960s and 1970s and how an idealistically rebellious young movement rejected the postwar industrialized food model of processed convenience foods and laid the foundations of the organic food craze, the burgeoning natural products industry, and the more conscious way Americans—and certainly Common Ground readers—attempt to eat.

Common Ground: [Laughing] Hippies and food—two of my favorite topics. In your words, what is a hippie?

Jonathan Kauffman: [Laughs] Also some of my favorite topics! Hippies were the psychedelic-influenced counterculture that erupted in the San Francisco Bay Area around 1965-1966. Their fashion and way of life, their ideas around freedom and self-expression, spread across the world.

What is hippie food and its significance?

I think that term came with my generation, X, those of us born in the 1970s. Hippie food is what we were calling what our parents served. I think of brown rice and tofu, stir-fries, whole-wheat bread, lentils, soups, yogurt and granola and alfalfa sprouts—what you could find in food co-ops or natural food stores in the 1970s. That food continues to stay with us but not in the form that it took in the 1970s. It was often very hearty, very brown, but influenced by international seasonings and flavors.

You suggest that eating brown rice and tofu was a “political act” in the same vein as wearing long hair or refusing to shave one’s armpits. What’s your premise?

So much of the diet that people adopted in the late ’60s and 1970s was a reaction against the status quo. You were eating brown rice not necessarily because you liked the taste, but because it wasn’t processed grain. You were buying wheat berries and grinding them into flour and baking whole-wheat bread out of a sense of discovery, yes, but also because you wanted the opposite of the fluffy white chemically enriched bread from the supermarket. At the beginning it was definitely function over form, idealism over taste.

Can you describe the context of industrialized food in that era?

Before researching the book I had little sense of just how much the 1940s and ’50s changed the food supply. After World War II agriculture became very dependent on tractors, machines, chemical fertilizers, and pesticides. Hundreds of new additives invented in the 1950s were going into the food supply. Tiny markets gave way to large supermarkets that required shelf-stable products. There were all these canned and frozen and boxed foods invented in the 1960s and promoted through recipes. Cooking became the combining of boxes and the baby boomers were the first generation to grow up entirely on that food.

What was Rachel Carson’s influence?

As the Baby Boom generation was growing up with all this packaged food they were also becoming aware of its downsides and dangers. Rachel Carson’s 1962 Silent Spring tracked the effect of DDT, the nation’s most commonly used pesticide. So the idea of DDT and chemicals lingering in the food supply and progressing up the food chain had a huge impact on America. It underscored the need to find a different path because people had no idea what they were doing to their bodies—and to other species—in the long term.

What about Frances Moore Lappé’s influence?

Diet for a Small Planet came out in 1971. To me it was the cornerstone book of this movement. Lappé researched and wrote it because she was concerned about global famine and with the idea that the world had reached its capacity to provide food. When she looked at agriculture reports and nutritional analyses, she discovered that America could actually feed the world if only we diverted to humans the grains and beans we were feeding to the animals we used for meat. The effect of that book was twofold. One was that a vegetarian movement erupted as a political choice. The second was that people began to look at food politically as they never had before. Her message was that our individual food buying choices have further reach and impact on the world.

Do you think the psychedelics used by the hippie movement had much influence on the food movement you describe?

On the initial movement I think it had some but more generally not so much. I talked to a number of people who were actual hippies in both the Midwest and in California who took LSD and their experience of oneness translated into not wanting to eat animals. Certainly at The Farm, the country’s biggest rural commune, which was started in San Francisco—some of their spiritual insights came from LSD, and they were vegan. But for people like my parents, for example—they adopted this diet while living in small-town Indiana and as far as I know never smoked pot, let alone tripped their brains out. I think the political and nutritional concerns ended up outweighing the psychedelic insights.

So the broader motto of the counterculture should have been Sex, Drugs, Rock ’n’ Roll, and Brown Bread?

[Laughs] Pretty much.

Do you have any sense of how the Beats who preceded the hippies ate?

I don’t. When I talked to people who lived in the Haight and were part of the psychedelic scene they described how hippies just ate what was cheap. Like hamburgers and a whole class of stoner foods—greasy, fatty, sugary foods that people who are stoned like to eat.

What can you say about the Diggers? I know they were offering free food in the Haight.

I ended up falling in love with the Diggers. They were kind of the radical edge of the psychedelic hippie movement. They advocated total freedom and may have come up with the phrase Today is the first day of the rest of your life. They did guerilla theater productions and distributed leaflets and had something called the Free Store where everything was free. They attempted to liberate people from their preconceived ideas.

They were also concerned about all the teenagers who were flooding into the Haight filled with idealism and absolutely no common sense. The Diggers set up crash pads to house them. In 1967 they started cooking stews every day and distributing them in the Panhandle. Then they added whole-wheat bread that they baked in coffee cans. To receive the food you would have to bring a bowl and a spoon and walk through this giant orange frame set up outside their station called the Free Frame of Reference. By just walking through it you were acknowledging that you were free and then everything you were eating was free.

Didn’t Indian spirituality bring some delicious vegetarian food to the scene?

I looked more generally at the influx of Indian spiritual traditions. The Baby Boom generation became fascinated with Indian spirituality thanks in part to the Beatles and their interest in Transcendental Meditation and their trips to India. In LA you had Yogi Bhajan and then the Society for Krishna Consciousness (the Hare Krishnas), who were active in many cities including those in the Bay Area. Many other spiritual teachers drew large followings in the 1970s. So along with Indian spirituality Americans embraced other aspects of Indian culture like Indian dress, Indian patterns but really specifically, Indian food. Because so many of these traditions were vegetarian the followers adopted vegetarian diets and learned to cook curry as a way of preparing delicious, healthy vegetarian food.

Many of the vegetarian restaurants were run by devotees.

That’s because spirituality and vegetarianism had been so intertwined in America for the past 150 years. The Seventh-Day Adventists began eating a vegetarian diet in the 1850s. This helped set the tone.

Can you describe the macrobiotic influence?

Macrobiotics was invented in the early 20th century by a Japanese man named George Ohsawa, who first came to the United States in 1960. He taught that the American diet was causing heart disease, obesity, and diabetes and he advocated a local, seasonal, organic diet based on whole grains. At the same time he combined it with his own interpretation of Eastern ideas around yin and yang. He would say you have to balance yin and yang in your diet to align your body with the universe. The macrobiotic diet was largely a Japanese peasant diet which was then interpreted by Americans who didn’t necessarily have any idea how to use these flavors. Macrobiotics introduced counterculture kids to tamari, miso, brown rice, bancha tea, umeboshi plums, and many other Japanese ingredients.

From my understanding, after the Summer of Love much of the original Haight scene disbanded into communes and triggered a back-to-the-land movement.

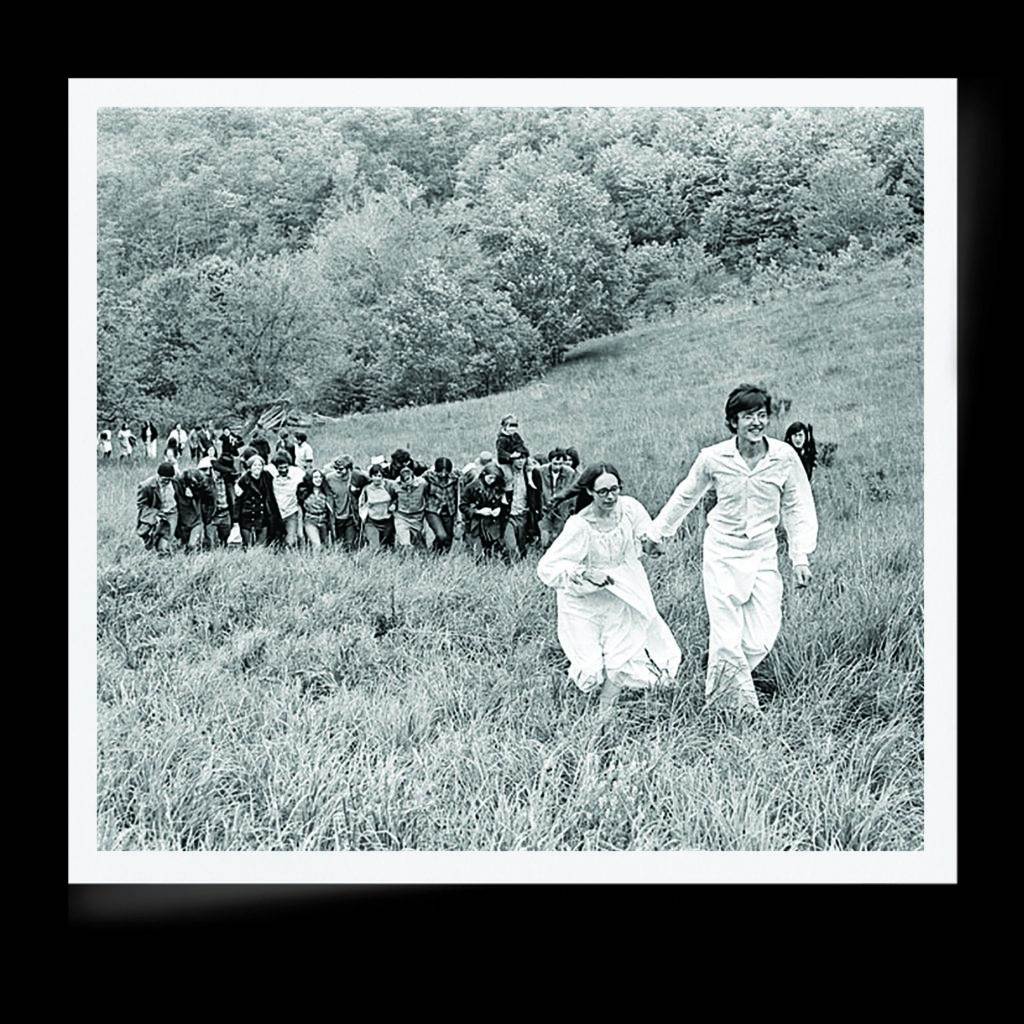

There have been several back-to-the-land movements in the United States, occurring in 30- to 50-year intervals. There was one around World War I focused on being economically self-sufficient, and another one in the ‘30s inspired by the Depression. The back-to-the-land movement in the 1970s was driven by counterculture kids who were disillusioned with politics and the idea that they could effect direct change on the political landscape. They wanted to create these new communities that were self-reliant and free from capitalism. So there was a huge outmigration from urban areas to rural areas. Along with the VW van that drove into tiny towns in Vermont or Sonoma County came all the ideas around natural foods that the counterculture was embracing. Many of the back-to-the-landers became organic farmers and helped build the backbone of the organic movement that we know today.

Many became successes in the natural products industry.

I interviewed Samuel Kaymen, who was an organic farmer in Vermont in the 1970s and ended up founding Stonyfield Farms yogurt. There were people like Mo Siegel who became a sort of divisive figure as the founder of Celestial Seasonings, which became the first big company to sell to one of the corporate giants. I talked to a couple of tofu makers including Seth Tibbott, who started making tempeh around the mid-1970s and later moved to Hood River, Oregon, where his company invented Tofurkey. In the Midwest, Eden Foods was part of the macrobiotic movement as followers of Michio Kushi in Boston and then moved to Michigan. They’re one of the few original natural foods companies that have remained independent.

Southern California had its own health craze pioneers with fruits and vegetables, especially given its conducive climate.

Decades before the counterculture emerged, tiny health food stores popped up all over the country. Southern California was a kind of headquarters of this health food movement, going back to the 1920s. It was very focused on vitamins and health and vitality and miracle cures and super food. Forward thinkers like Paul Bragg and Adelle Davis and Gayelord Hauser promoted health and beauty to people who would eat whole grains, integrating those with super foods like yogurt, wheat germ, molasses, and brewer’s yeast to give additional nutrition. They advocated drinking lots of juice and eating lots of raw salads, which was possible all year round in Southern California. There was a raw food restaurant in LA in the 1920s.

Here in the Bay Area we have famous food co-ops like Rainbow Grocery and the old Berkeley Food Co-op. Can you talk about the relevance of food co-ops?

There’s been a long tradition of food co-ops in this country. Many people remember the Berkeley Food Co-Op, which started in the ‘30s and lasted until the ‘80s. By the time the counterculture came around these had mostly become grocery stores. The counterculture kids started food-buying clubs and food conspiracies to pool their money to buy bulk goods and natural food staples that they couldn’t get in grocery stores.

Food conspiracies took off in San Francisco and Berkeley, in particular, where there were hundreds of them. All around the country those conspiracies and clubs evolved into small food co-ops where you would have to work as part of your membership to get discounts on foods and it was all bulk bins and jars and whatever natural products they could find. They were really devoted to the foods that you couldn’t find anywhere else and they wouldn’t carry anything like sugar or refined flour. Up to about 5,000 of those sprang up around the country over the course of the 1970s.

in a 1973 clipping from the Elkhart Truth.

What prompted you to write about hippie food?

It was a curiosity about my own childhood because I had not given it much thought until about 10 years ago when I was eating at a vegetarian café that had been around for about 30 years and realized how nostalgic I felt toward it. That cuisine was disappearing in the form that I remembered it. I began wondering about the politics of food and why were we eating alfalfa sprouts and carob and granola in the first place?

Can you talk about growing up in Indiana and how it influenced your work?

My family is Mennonite. My parents were the first generation to go to college and live in urban areas. They were politically and socially very liberal and weren’t into drugs and rock ‘n roll or sleeping with everybody. Instead, they were active in social justice and peace issues. In the mid-1970s there was a cookbook that came out in Mennonite circles called MoreWith-Less that was inspired by Diet for a Small Planet. My parents really took to this idea that they could have a diet that was as steeped in social justice as the rest of their lives. It combined these hearty brown foods with international flavors and advocated this simple cuisine as a way of living more lightly in the world. My friends and peers all grew up eating lentil stews and none of the German foods that my parents grew up with.

Can you talk about what it is to be Mennonite?

That has really changed over the years but the core tenet that continues to separate Mennonites from other Protestants is the belief in nonresistance to violence—like a more radical pacifism. Mennonites are Anabaptists and aren’t baptized as kids; you have to choose your faith. Then it’s this belief that the church community and your devotion to God takes precedence over your involvement in political matters and the broader culture. Traditionally Mennonites didn’t vote—we are all conscientious objectors. But in my generation more and more Mennonites are getting involved in the world as a way of doing some good in it.

What is the distinction between Mennonites and the Amish?

The sects split off from each other in 1693, but they have always existed together or around each other. The Amish practice an even more radical form of absenting themselves from the world including their dress and their speech—Pennsylvania Dutch—and in their devotion to a lot of rules taken from the Old Testament. [Laughs] I compare the Amish to ultra-orthodox Jews and Mennonites to reformed Jews.

You’re openly gay. What was it like to be young and gay and Mennonite?

I’m no longer Mennonite, which tells you a few things. Back in the ’80s and ’90s when I came out it was definitely stigmatized. My parents’ church was one of the first churches in Indiana to vote that sexual orientation should not be a criterion for disbarring a member. So there is a whole open and affirming movement in the Mennonite church that has now grown much better than it was back then. I went to a nonMennonite school in the Twin Cities and then moved to San Francisco as a way to be a bigger person and have a bigger life than the life I could have in the Mennonite church.

What did you study in college and how did you end up becoming a food writer?

I majored in comparative religious studies. I never connected that to my family until much later when I took my husband to a family reunion and about a third of the adults were ordained pastors. He was like, “Oh, you just joined the family business.” I didn’t end up doing anything with the comparative religions degree. I moved to San Francisco in 1993 and ended up cooking. I had fallen in love with cooking in college and cooked in restaurants here until I decided I didn’t want to work in the restaurant industry. I was training as an editor when a friend of mine who wrote for the East Bay Express said, “Hey, they’re looking for freelance writers to write about food. You should try something.” So I pitched a piece to them and they bought it. Two and half years later they hired me as the full-time restaurant critic.

Now you work at the San Francisco Chronicle and your colleague Michael Bauer is very popular reviewing haute cuisine. How would you contextualize the trend of upscale restaurants in America? It seems there’s an endless appetite for Michelin stars.

Fine dining became democratized in the 1980s, spreading beyond just the rich. Then it became entertainment in the 2000s. Now it’s like a major part of pop culture thanks in part to The Food Network and other television channels. People eat out and change restaurants for entertainment. They want to snap photos of their food and post them on social media. That’s been a big shift.

Is there any correlation to the hippie food movement?

It’s the antithesis, actually. Hippie food was a populist movement with a cuisine created by and for people who didn’t have a lot of money. It was about sustenance nourishing. The hippie food restaurants became social centers but it was an anti-capitalist movement. One of the big mottos of food co-op movements was Food for people, not for profit. They would be horrified by the bourgeois spectacle of high-end dining today.

You write, “Americans have a queer eagerness to abandon the culinary wisdom of the generations that preceded them.” Can you talk about that? And where do you think we’re going?

Because of the melting pot philosophy embedded in American life we shed our culinary roots very quickly over the course of just a generation or two. As our families moved off of farms and into cities that left us with only what we could find in American supermarkets. We’ve lost our traditions around eating and turned to science and fashion to teach us what we should eat. By science I mean both the sound nutritional advice we get but also the pseudoscience that comes with any new idea that’s promising a miracle cure to make us healthier or smarter or sharper. We tend to just rush to embrace trends before considering whether they will be effective.

Going forward, I think people will end up laughing at a lot of the trends that Americans have picked up along the way. But I also think they are this potent generative force in American cooking. Even though some of the diets that drive us to adopt new flavors and ingredients are specious, they produce a lot of really interesting ideas and move the cuisine along. Look at the paleo movement or the vegan movement or the gluten-free movement that’s disconnected from celiac disease. I see a lot of culinary creativity that will continue from those. In 30 years, even if we’ve forgotten what gluten-free was, there will be all of these dishes that we’re eating because they were introduced during this time.

What is the core message of Hippie Food, boiled down?

I’m hoping people will re-appreciate this food they used to eat or grew up eating but have since pooh-poohed. I think that the counterculture of the ‘70s introduced a critique of industrialized food that is just as trenchant today as it was in the 1970s. And even if they didn’t get everybody to shop at food co-ops or eat vegetarian food or nutritional yeast, they created this healthy everyday diet that has become the template for an alternative to avoid processed meats.

Congratulations. The book is getting terrific coverage. I think you’re onto something. What’s the effect so far?

It’s only been a month so I think it’s too soon to see if it has larger effects. For me personally it’s been a huge validation after five years of work. I’ve been really grateful that people are finding the stories as interesting as I did when I stumbled upon them.

What are your next projects?

My full-time job is with the San Francisco Chronicle in the Food section and so I am re-turning 100% of my attention to that. One project I led there was a guide to regional Chinese cuisines in the Bay Area. It’s a look at how Chinese cuisine has diversified here because of immigration patterns and how we once just had Cantonese and Chinese American food. Now we have Szechuan and Shanghai and Yunnan and Shaanxi and all this regional cooking here in the States.

Besides food what are your other passions?

When I was a religious studies major we were reading a number of texts by Dōgen Kigen who is the founder of Soto Zen and I got really interested. The philosophy sat there with me but it took another 10 or 15 years before I began sitting. I sit zazen every day and am a member of the San Francisco Zen Center, which is a big part of my life. What I discovered through sitting is its real effect on how I respond to the world around me and to my own emotional response to events. It’s one of the things that keep me sane.

I imagine you’ve spent time at Green Gulch Farm and understand the context of the whole Tassajara Bread Book phenomenon. Can you speak about Zen culture as it relates to food?

One of the pleasant surprises I had while I was doing this research was how connected the San Francisco Zen Center was to this food movement. Edward Espe Brown, who was the first head monastery cook at Tassajara and wrote the Tassajara Bread Book, taught people how to bake whole-wheat bread. He gave them a great recipe but then also taught them the sensory skills they needed to be able to bake.

One of his roommates at Tassajara, Bill Shurtleff, moved to Japan in 1970 to set up a meditation center for visiting Americans who wanted to study Zen. And when the founder of the Zen Center, Shunryu Suzuki Roshi, died he was kind of cast adrift. Because of his reading Diet for a Small Planet he got interested in tofu and he and his partner and then wife Akiko Aoyagi wrote The Book of Tofu and The Book of Miso. They traveled the United States inspiring the emergence of dozens of tofu shops. I think people’s interest in Asian spirituality led people to be interested in other aspects such as traditional Chinese medicine, aikido, shiatsu massage, and Japanese flavors.

Are there any turnoffs you find in current food trends?

I’m not thrilled by what I call “dude food”—the super-fried food on top of pork belly on top of mayonnaise. It’s the kind of stoner food that I don’t think is particularly delicious but people seem to want to eat as a dare. I think some of the Instagram-oriented foods like the rainbow bagel and anything that’s only for visual effect but doesn’t make the food taste good is annoying. I’m all about taste.

Do you gravitate to vegetarianism or veganism?

I do even though I’m omnivorous and eat everything. Like last night I had tripe and squid and beef tongue, but my husband is vegetarian so at home we cook vegetarian.

Can you share a final message for readers, many of whom are ex-hippies or wannabe hippies?

What I loved about this book is that it’s celebrating the fringe. It’s really about all these fringe ideas—some of them very kooky—that people rushed to embrace in the 1960s and ‘70s as they were trying out all these different ideas and diets and ways of life. For all their kookiness each of them ended up having these cores of wisdom that the counterculture extracted. This all created a new vision of what is a healthy cuisine. So I fell in love with all those folks who preceded the hippies and I hope readers do, too.

Rob Sidon is publisher and editor in chief of Common Ground.