Spring-Loaded

for Supernormal

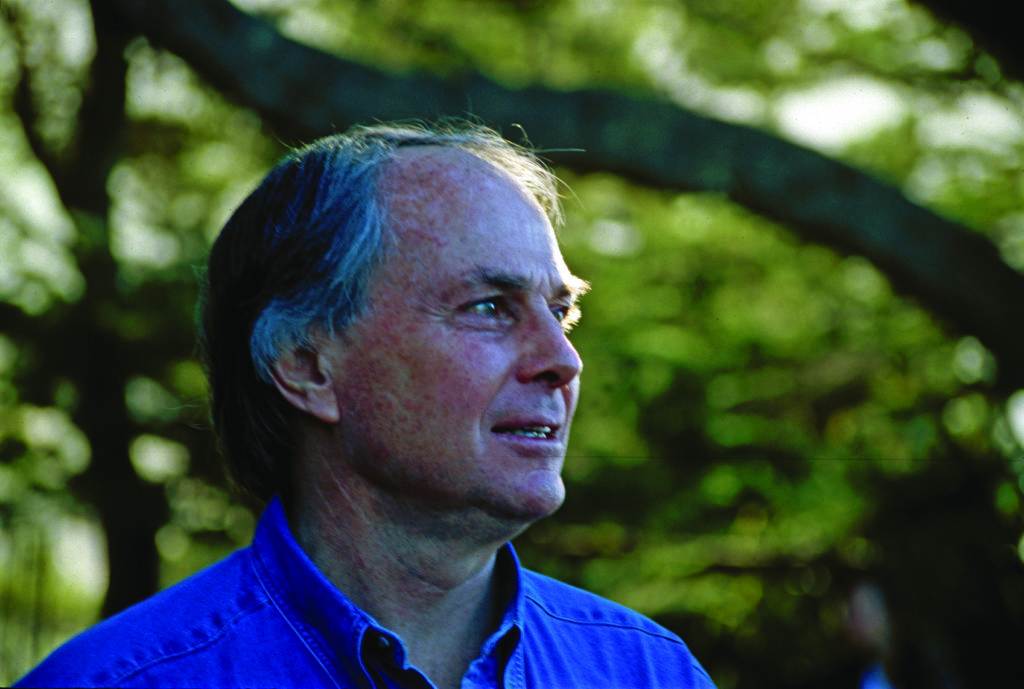

Michael Murphy was born in 1930 to a prominent family in Salinas, and took an early interest in both sports and religion. He started on the premed fraternity path at Stanford but radically switched to become a yogi after stumbling into a comparative religion class taught by Frederic Spiegelberg. This kind of behavior was unheard of in Salinas in the early 1950s and the family was moved to sue both Stanford and Spiegelberg. Eventually they desisted and came to accept their son’s vow of chastity and his daily routine of deep meditation lasting from six to eight hours.

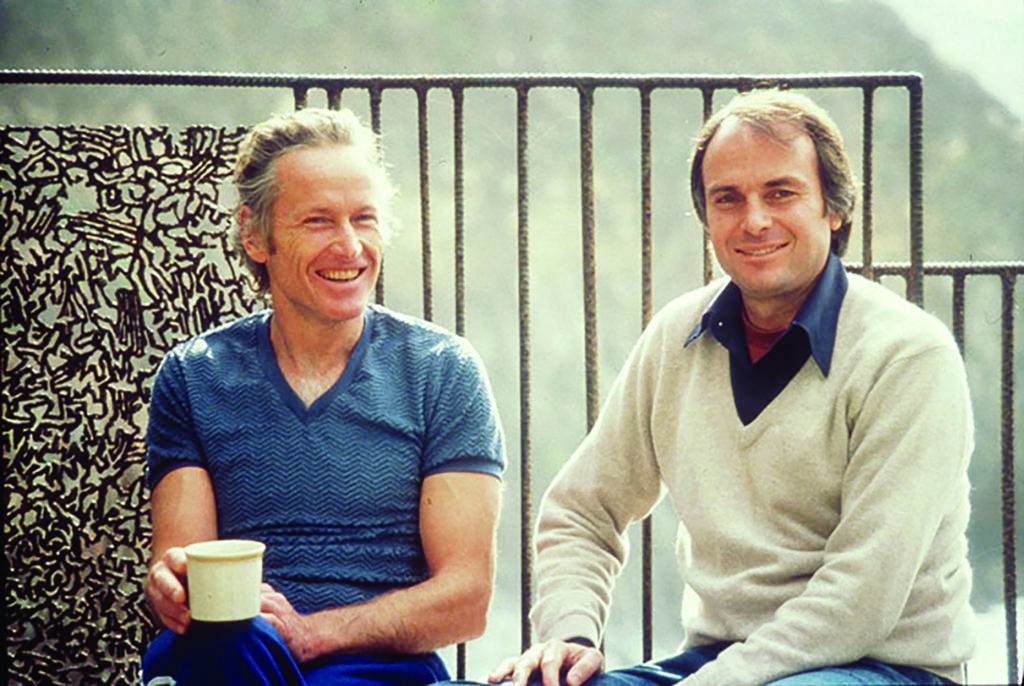

After an Army stint during the Korean War and an extended visit to the Sri Aurobindo ashram in India, Murphy returned to San Francisco, where he paired up with Dick Price, a spiritually inclined Stanford classmate. Together they started Esalen Institute in 1962 on the Big Sur property owned by Murphy’s fiery then 90-year-old grandmother.

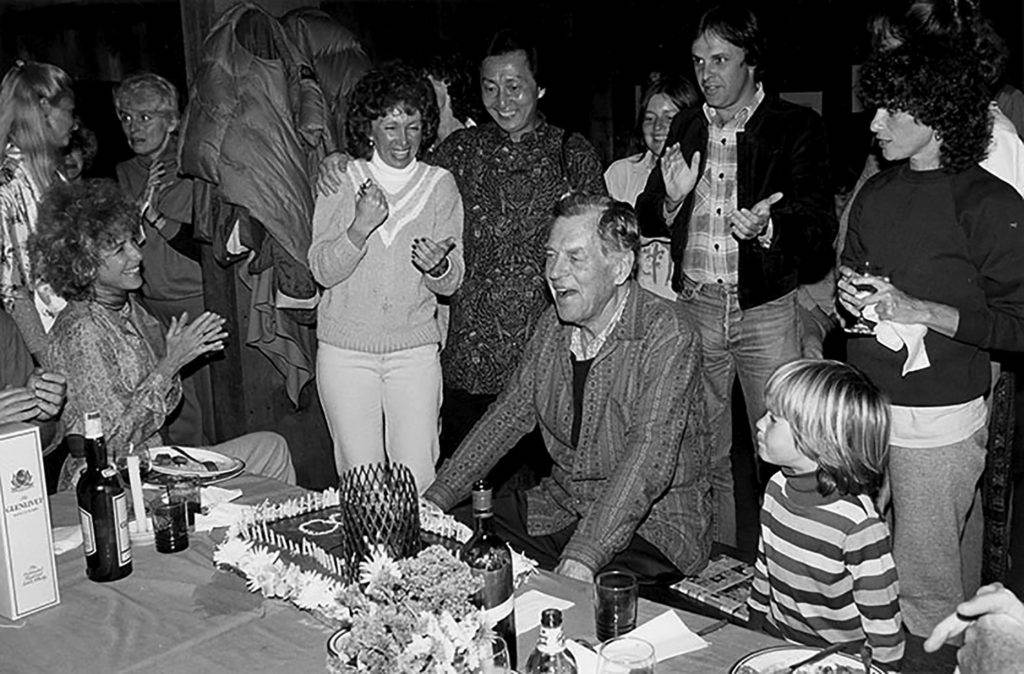

Esalen quickly became famous as a progressive international hub that attracted A-list artists, celebrities, and intellectuals (far too many to list) from a wide range of disciplines. It became identified (and mis-identified) with a number of pioneering movements, notably the Human Potential Movement and its many spinoffs. By any yardstick Murphy is a spiritual philosopher and mystic, yet he was schooled in boxing by his own father and claims this tutelage influenced his ability to defend Esalen’s fierce independence for nearly six decades. Dick Price died while hiking in 1985.

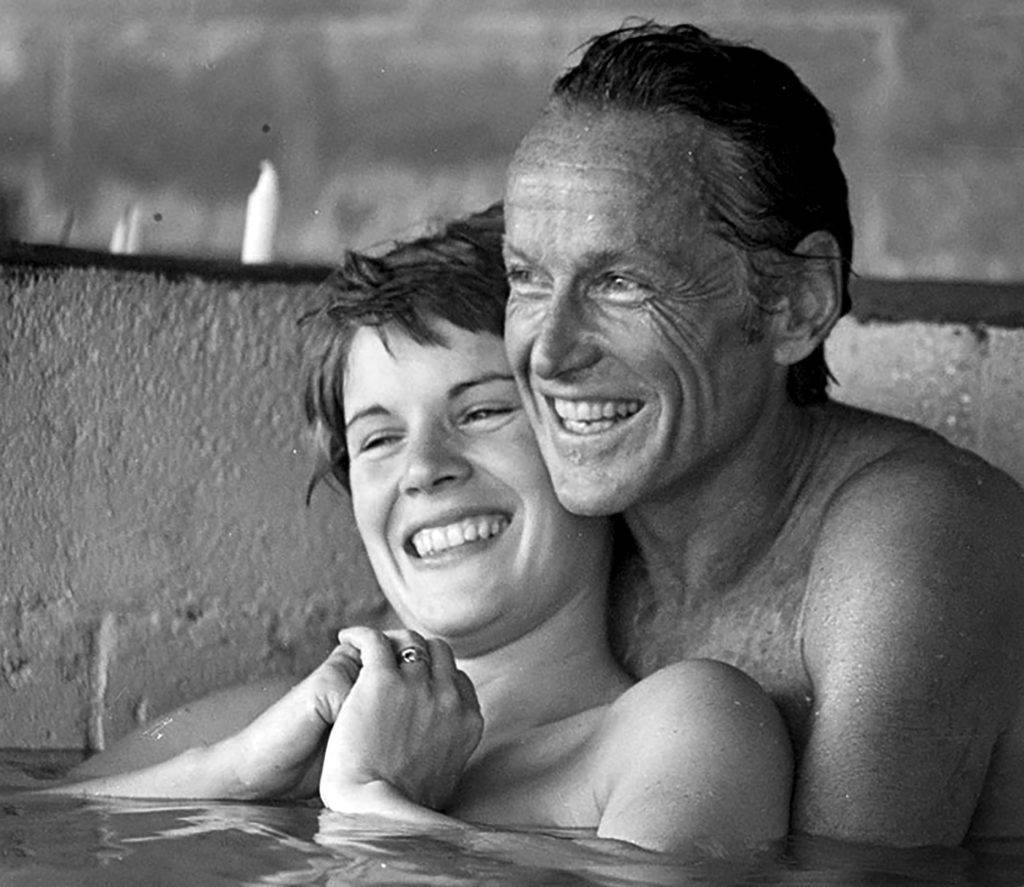

Murphy has written many books, including Golf in the Kingdom and The Future of the Body. He and his wife, Dulce, support a broad range of research initiatives and have long been on the frontlines of Track Two citizen diplomacy aimed at improving strained relations between nations, notably the US and Russia and the former Soviet Union, through influential nongovernmental backchannels. Late in life they had a son, Mac. They live in Mill Valley, CA, where we caught up with them.

Common Ground: Can you tell the story of growing up in rural Salinas?

Michael Murphy: I had a very fortunate childhood and upbringing. My father’s family landed in Salinas in the 1890s and my grandfather was a much-loved doctor who built two hospitals there. In many ways it was an archetypal Scots-Irish family that put a premium on storytelling. My grandmother was quite a character—a redhead with four redheaded kids. My grandfather delivered John Steinbeck, who became a lifelong friend of my father’s. Reading and storytelling were in the air. My father was a lawyer. My brother was designated to become a writer and I was to be a doctor.

Sports were important?

Sports were a huge thing for us. My brother Denny and I were good athletes and we both had to learn to box as kids because my father boxed at Stanford. He actually had three professional fights and won all three. By the time I was 15 I hated blows to the head so I quit. We would ride horses in the rodeo and slide off these horses to wrestle little calves. It was a kind of kids’ version of steer wrestling. I started golf at 14, which is late to start golf, but I got good enough to compete in tournaments.

Steinbeck’s Salinas was a tough town, no?

A tough cow town of growers down there—very different from what it is now. I got a good look at the kinds of things Steinbeck was writing about in The Grapes of Wrath and his subsequent books. For example there were big strikes with the Okies who came from the Dust Bowl. In the late ’30s Harry Bridges’ communists came down and took sides with them against the growers. My father moved us kids out of town to be out of harm’s way. On another occasion a Chinese tong [gang] came down from San Francisco and killed many of the Chinese in Salinas—a mass shooting. Americans forget their history and how violent things were. Al Capone was running things in Chicago and ended up here at Alcatraz. Baby Face Nelson was hanging around Sausalito.

I grew up with a certain safety but also an awareness of how tough it was. After my first broken nose in boxing my father actually said, “Mike, you need one more to be a better-looking guy.” He said, “You’re a peaceable guy; you don’t have to fight. But if you do, you learn to break their nose with the first punch” [laughs]. This was his enduring lesson that I prize because we’ve had lots of fights at Esalen Institute. I’ve never had to break anybody’s nose physically but yes—metaphorically. You’d be surprised at our feisty history [laughter].

What was your religious upbringing?

I was the only churchgoer in the family and became an altar boy. Originally my grandmother took us to the Episcopal Church. My father’s side—he was heavily skeptical, being a lawyer. It was Mark Twain and Clarence Darrow and HL Mencken. My mother was Catholic. Her family was from the French Pyrenees. She was clearly psychic, but not a churchgoer. During summer church retreats I’d get it into my mind that I was going to become a minister. My family did not want me to be a minister [laughs].

Thinking back I was a very religious kid but, honest to God, can never remember praying to Jesus—it was God. I just couldn’t buy the stuff about angels and the Virgin Mary. I somehow picked up Will Durant [The Story of Philosophy] and was quoting Spinoza as if I understood him. I didn’t but his high panentheism appealed to me, his kind of mysticism.

So you went to Stanford to become a doctor.

I’d gotten interested in psychology and becoming a psychiatrist but in my sophomore year I stumbled into a lecture by Professor Frederic Spiegelberg, who taught comparative religion. He was popular at Stanford. I’ll never forget the first time I saw him, when he came before 600 students in the auditorium in total silence. He didn’t say a word and had everyone’s attention and then in a big voice said, “BRAHMAN.” Well, I was lit up.

That was the first word he uttered?

The first word he said—BRAHMAN [booming voice]. He was lecturing on the Vedic hymns. By the end of this hour walking back up to the fraternity—I mean the wet head was not dead—I was still a slicked-back Stanford student but the thought dawned on me: “I’m never going to be the same.” It changed my life. I was filled with a fire, particularly for the work of Sri Aurobindo’s Life Divine, which I read that summer. I started to meditate and was playing golf in a half-stoned state. My younger brother pronounced that I’d become a “Golfing Yogi.” This fire grew to such an extent that during my junior year I quit premed. I quit the fraternity and my family almost went into shock. In those days in Salinas nobody knew what a yogi was, except as somebody who laid on a bed of nails and looked at the sun [laughs].

At Stanford they let their good students do “directed reading” and Spiegelberg became my primary advisor. I read what I wanted and got the credits to graduate. I read heavily into the various subjects that eventually flowed into Esalen.

Did you have the support of your family as you were becoming an esoteric contemplative?

When my father saw what was going on he said, “While you’re at it, son—you’ve dropped out of your fraternity, dropped out of premed, now you drop out of the Murphys.” He said it that way. “No more money from us.” At first he was going to sue Stanford and sue Spiegelberg but he didn’t. And later when I was in the Army in 1955 I got a check in the mail for $5,000, which today would be like $50,000. The note said, “In case you want to go to India.”

What happened?

They loved me and got used to it. They just came around. Eventually my dad became the lawyer for Esalen.

Let’s hear the Esalen story. You and Dick Price had the idea. How did you connect with him?

After college I joined the Army during the Korean War and had the easiest job, stationed in Puerto Rico—fighting mosquitoes [laughs]. It was a time when I could read and meditate and do sports. Back then I used to meditate for many hours every day. Afterwards I went back to Stanford for awhile and eventually to India to be at the Aurobindo ashram. After India I was still finding my way in San Francisco. I didn’t know it yet but I had already developed this idea for Esalen.

Dick and I had been classmates at Stanford but didn’t know each other as he had his own evolution. He had been aware of me because I had been a campus hotdog and had won elections as student rep and people thought I should run for student body president. He knew that I had flipped to become this yogi. It turns out he too had flipped with Spiegelberg at Stanford and after graduation was going around with Alan Watts. Then in ‘56 Dick went into the Air Force but had a far different experience than I had in the Army in Puerto Rico. He too had lit up spiritually but in a way that put him in the brig, the military mental hospital.

Dick’s father was the executive vice president of Sears and Roebuck, which was a big deal then, and was a friend of Stuart Symington, the Secretary of War. They got him an honorable discharge on the condition that Dick get out of this state. He ended up in the Institute for Living [a private mental facility in Hartford]. Did you ever see A Beautiful Mind, about John Nash? Well, he was there at the same time. The horror of it, Rob! He suffered 67 insulin shock treatments. Finally he got out and recovered and heard about me living in San Francisco and came there to find his next step.

I was living at this place on Third and Fulton which was like a mini ashram, owned by Haridas Chowdhury, a prominent brilliant young professor from Calcutta, the founder of the California Institute of Integral Studies. So when Dick came I said, “Why don’t you move in?” He did and then we went down for a retreat at the Big Sur property that my grandmother owned. And then the adventure started. We were both 30. You must have heard some of these stories, with Hunter S. Thompson?

No, but I would love to hear the early stories about your grandmother’s property and Hunter S. Thompson.

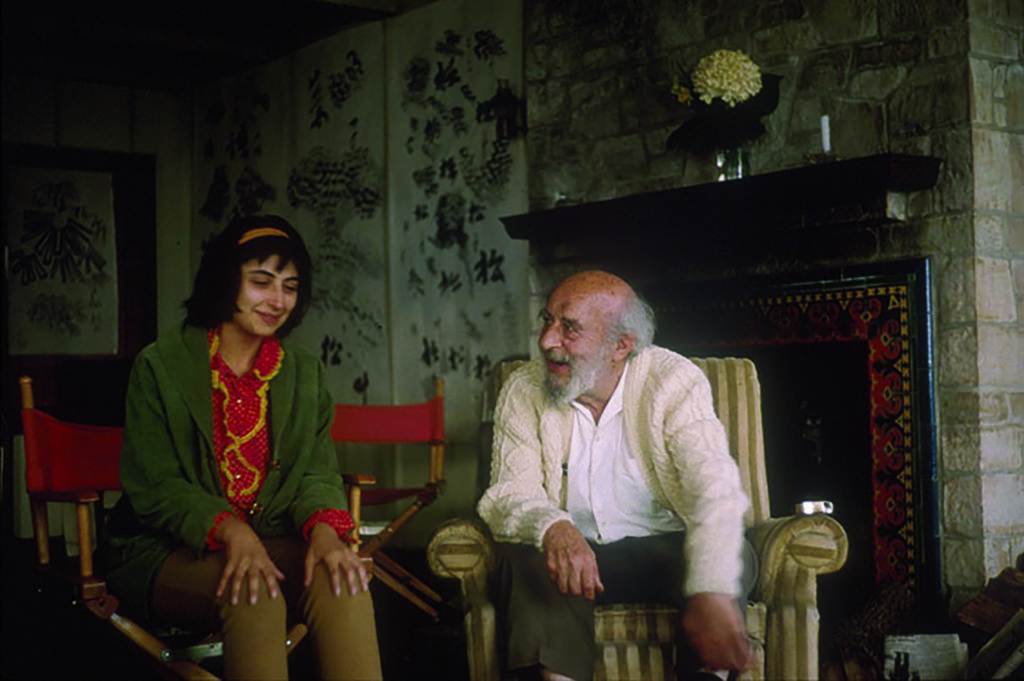

My grandfather died after the war and my grandmother fiercely managed the mini property empire that included this Big Sur property. She was a character—a very Victorian woman and kind of intimidating. She had one good eye that was forbidding when she looked at you [laughs]. She promised she would never sell the property even though there had been a lot of offers—from the Pebble Beach Company. D.H. Lawrence’s wife Frieda had come around to buy it. She came with her husband’s ashes in a jar.

By this time my grandmother was close to 90. I tried to see if I could take it over but she said no. She told everyone, “If we ever give this property to Michael he will give it to the Hindus” [laughs]. She was the boss, the godmother, and my father was her consigliere. She wouldn’t let him take over either, and she hired a 21-year-old Hunter Thompson to be the caretaker of the place.

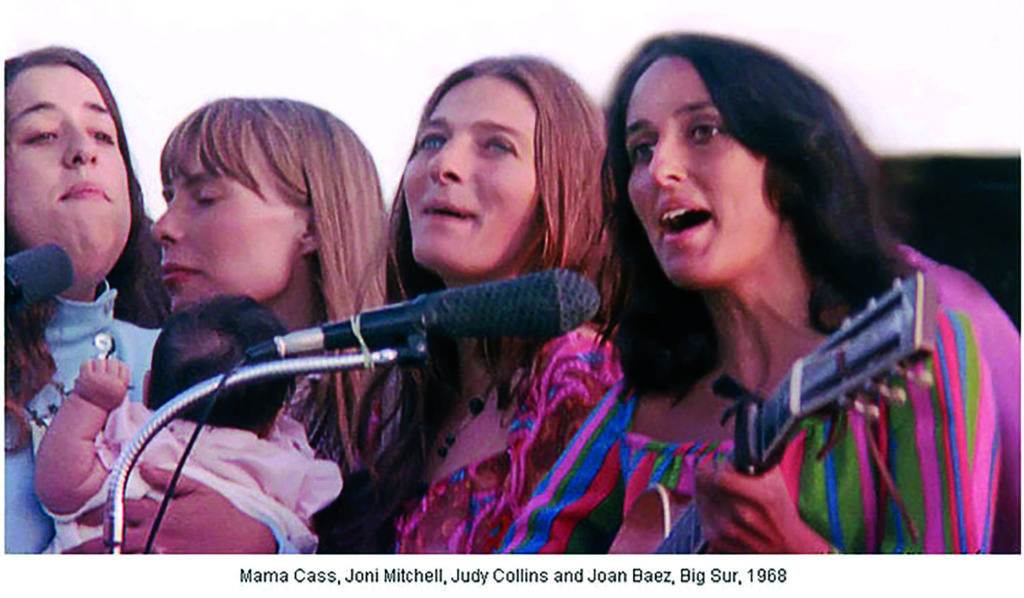

Thompson wanted to be a writer and was originally attracted out here because he admired my brother Dennis, who had already written a bestselling novel [The Sergeant], and ended up getting this job from my grandmother. When Dick and I went there a 19-year-old Joan Baez was living in one of the cabins. No one knew who she was. Henry Miller would be down there four or five times a week bringing celebrities like Anaïs Nin and Lawrence Durrell.

Were they just squatting on the property?

No, they would come down to the baths during the day. Hunter was living in wing of the old family house with his lady friend, writing his novel and wondering who we were. I had to convince him that I was part of the family. Hell, he had an arsenal of weapons—tracer bullets by the hundreds! What happened is that on weekends this Muscle Beach gay crowd would literally take ownership of the baths. One night they tried to kill Hunter. They grabbed him and were going to swing him over the cliff. Fortunately Hunter was pals with another woman, not his lady friend, who was about 250 pounds and could land a haymaker with a billy club [laughs]. The two of them had to fight their way out of this gay gang. And there was also this Pentecostal group to whom my grandmother leased the property. Anyway, the next day there was gunfire. Hunter was shooting into the bushes because he thought they were coming to get him. So I said, “It’s time to tell my grandmother what’s going on down here.”

Then my father got into the act and said, “We’d better let Mike take over this property because otherwise we’re all going to be in jail together.” It was out of control. My grandmother kicked Hunter off the property and eventually the Pentecostals left.

What was your impression of Hunter Thompson?

[laughs] A very spirited guy to say the least! Out of the hills of Kentucky, 6’3″, broad shouldered, lean, fully armed, high jest crazy in a gonzo sense—but serious about writing. He would take a novel and copy it longhand, just to get the feeling of it. He had done that with my brother’s novel. He did it with Hemingway and other writers. He turned out a lot of books that still age well. The whole Beat thing was going on with its off-kilter surrealism but intellectually I would not put Hunter with the Beats—he was a true original.

The madness [laughs]! One time his buddy John Clancy, who later became our lawyer, was getting married on the property and their best man was a goat. They had dressed it in a necktie and glasses! And Hunter was making beer. But the problem was half his beer bottles would explode all over the place!

Another time Dulce and I visited him in Aspen and he was firing hundreds of tracer bullets over John Denver’s house—they were raining down in the night sky. It was like the bombing of London! He must’ve had a supernormal liver because he drank a lot and took lots of drugs.

Did you know Neal Cassidy?

No, I never knew Cassidy, but I did get to know Ken Kesey from Stanford. They came down on the Merry Prankster bus but I never got in with that crowd. For some reason the Grateful Dead never came.

Did you tap into the psychedelic culture of the time?

It never really worked for me. I only did it about eight times. I had an intuition that it wasn’t good for my brain but people were getting stoned there all the time. Aldous Huxley and his wife Laura gave me LSD for the first time in Mexico when we started Esalen. They had the pills from Sandoz. Huxley died in ‘63 but said many things to me and was a big influence on us. We named our main meeting room “Huxley.”

On another occasion I remember roaring around the place with Dick Alpert and Tim Leary but that’s a whole other story [laughs]. We had a lot of dealings with Tim and helped him while he was in prison. I saw him off and on until he died.

Michael Pollan’s new book [How to Change Your Mind: What the New Science of Psychedelics Teaches Us] gives Esalen credit for keeping alive the serious reconsideration of federal drug policy. We had a seminal conference in 1998 that led to the Johns Hopkins research. Esalen brokered a lot of stuff that’s never been described before, much of it documented in a big book [Esalen: America and the Religion of No Religion] by Jeff Kripal.

You never had problems with the law?

In ’64 I met the head of the DEA for Northern California, who taught me about the Fourth Amendment, against search and seizure, habeas corpus—a basic reason for the American Revolution. I mean we colonists had slaves but we were also slaves—to the British [laughs]. Anyway, the Fourth Amendment says that no one can tell people what to do without a warrant from a court. He informed me that this applied to innkeepers as well as to the police. He said, “If you try to regulate your guests they’re going to sue the hell out of you and they will win.” He said, “Your responsibility is to make sure the dealers never come there. We will hold you responsible for that—and [pause] we know all about you.”

What follows is one of my favorite stories where I earned my spurs with the community because of Big Bad Bill, who was 6’4″, built out always with a tight black T-shirt, black hat, and he was the biggest and most prominent dealer walking around the property.

Word got out that I had to tell him that he could never come back and everybody was wondering who was going to win this one—little Mikey or Big Bad Bill? But I looked him in the eye and said, “You can’t come back on this property again. The DEA knows you’re here [dramatic pause]. In fact they’re watching us right now.” I lied but he believed me. He nods and says, “Thank you”—then stood up and walked away, and everybody’s going “Whoah!”

Then we started having Joan Baez folk festivals out on the deck of the swimming pool. By then she had gotten famous. When she sang at Esalen her extraordinary voice hit those high notes and—you won’t believe this—there would be a four- or five-second resonance down the coast. And the marijuana smoke billowed…and up on the perimeter Highway Patrolmen and DEA guys…letting us be…but ever watchful. Thankfully we never had an arrest on the property. There has never been a murder. In those early years there was an element of miracle that we got through alive.

Where were you during this time? Where was your spirit? Your ego?

Good question. I was old in certain ways. I mean I was keenly aware of the metaphysical baloney that comes down on all sides because I had read so much about it. But Dick and I were also very young with no business experience. It was a huge new adventure that lit up my entrepreneurial side. If I simply read somebody’s book and then wrote to invite them—they came. So I got to meet my heroes—and also see how human they were!

I wasn’t meditating six or eight hours anymore but I was on fire in a different way. Instead of a Jnana yogi [path of knowledge] I became a Karma yogi [path of action] of a certain Tantric persuasion. That’s a long story. Sexually I was a virgin until I was 32 so I was still a virgin when Esalen started. I had a couple of royal misadventures on the erotic side, including a marriage that lasted three months. We eloped to Sparks, Nevada, and I woke up the next day going, “Gee, how did that happen?” [laughs]

[in disbelief] How did you manage to maintain your virginity until you were 32?

Well, basically our gang in high school didn’t play spin the bottle and didn’t fuck. I was popular with the girls but was religious and also hated the whole idea of going steady, the whole trading rings thing. At Stanford it was basically the same dynamic. But after my sophomore year with Spiegelberg—which was a huge influence—and Aurobindo, the guru, who advocated “No sex”—well, you’re just going to have to believe it: I took vows of chastity. I said, “I am going to go for it.” I was 20 and I maintained it until 32. At Esalen once it [sex] started I found it hard to stop.

Did Esalen identify more with the Beats or the hippies?

Neither. Jack Kerouac had written a book, Big Sur, in the ‘50s and he described the property before it was Esalen. Then in Esalen’s earliest years Allen Ginsberg, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Michael McClure, David Meltzer, and other poets whose books were at City Lights bookstore did readings. We had a regular series in those years with Ginsberg, Gary Snyder, Bishop Pike, and Alan Watts. The four of them did a rip-roaring seminar in 1963. So traces of the San Francisco Renaissance or the Beat Generation were evident but I have to resist labels. I prefer to say Esalen Institute is a complex place [laughs].

For example, one afternoon in 1962, on one half of the property you had Arnold Toynbee, the famous historian, talking about the coming of Buddhism to the West. It looked like the mid-‘50s. All the attendees were wearing neckties. And simultaneously on the other side of the property Allen Ginsberg was reading poetry and most of the folks were half naked. The word “hippie” was not invented until 1967 and when it was Esalen got mislabeled “sex, drugs, and rock ’n’ roll” because we had a center in San Francisco by then and the media picked up on it.

Esalen did become the de facto headquarters for the Human Potential Movement and was tagged with the Gestalt-Fritz Perls connection.

That’s another over-identification. Fritz Perls was a wicked genius. He had a supreme gift. He’d look at you and instantly know more than you wanted to know—and then he would tell you. There are people like this. Esalen gave him a base of support and brokered his emergence and fame. In fact he probably came closer than anyone to “capturing the flag” through his influence on people, including Dick. In the early ‘60s it was so fluid what happened inside and outside the seminar rooms. You’d have Fritz coming up, very confrontational, right in the dining room, and he’d sit down and look you over and make some remark. It could even be nasty. And boy, it would stay with you because he’d invariably hit the mark. A lot of people, when they saw him coming—they would duck! But he was also an extremely creative innovator in the field of therapy. Since his death in 1970 Gestalt therapy has evolved and morphed to become more relationshipbased, kinder and smarter and better. Gordon Wheeler, who is the current president of Esalen, has been a central leader of its development.

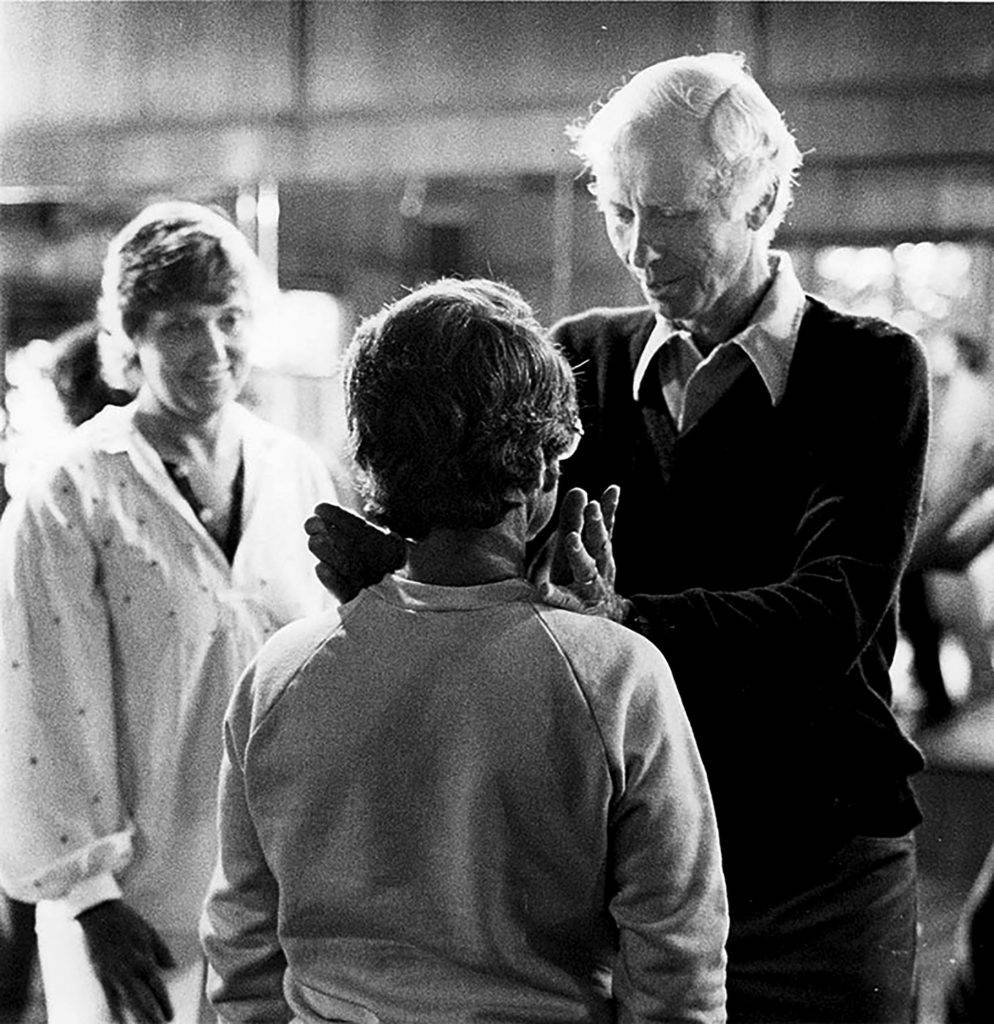

Esalen was a place for education.

Yes, it was never a hospital or a place for therapy. “Education of the whole person” we’d say—educating emotional intelligence to broaden one’s behavioral repertoire. Therapy by implication means you’re there as a sick person with symptoms. Now, people do come with illnesses and sickness and psychological problems, but our whole thrust was that therapy would get done in the wake of education.

You had high standards. One needed high educational credentials to run a seminar there, right?

From day one we labored to have the best teachers we could get, like any college or university. We’ve said no to far more people than we’ve said yes. But how do we judge? We did get some characters there. You and I both know many creative people on meds. Sometimes given the environment at Esalen, they start to feel great and decide to go off their meds—and pretty soon they’re standing on a bench doing this [pretending to fly]! So you have to deal with them kindly, yet be tough enough to take down someone who gets violent and haul them away while observing their legal rights. Fortunately we never had a malpractice suit.

Golf in the Kingdom came out in 1972. What is the premise?

In simple terms it’s a tall Irish tale, a fiction that kind of came to me. Michael Murphy is on his way to an Indian ashram in search of the greater human nature but thinks he’ll play one last round of golf at the links of Burning Bush. Unbeknownst to him he’s put in with a golf professional, Shivas Irons, who is a shaman. Over the course of 24 hours Shivas implicitly invites him to enter the mysteries with him but oh no, Murphy first has to go to India to find it. So he walks right past the doorway to enlightenment that’s there for him. This is what many of us do. We are all born to this possibility. It beckons to us and we walk past it—while it’s hiding in plain sight.

It was the first book I tried to write and it was never edited. It’s been translated into 12 languages and sold close to 2 million copies and is arguably the best-selling golf fiction book. It’s become a catalyst for sports psychologists looking at the mental game, the inner game. For me it has opened doors I never would have imagined. For example, John Brodie, who played quarterback for the 49ers, reached out to collaborate. It led to a sequel called In the Zone: Transcendent Experience in Sports and more importantly to my big book, The Future of the Body.

The Future of the Body is a sophisticated philosophical treatise that in many ways describes the endless potential of being in the zone, no?

The idea is that we are spring-loaded for supernormal life but our parents and our coaches and our priests didn’t tell us. And we all walk through life accommodating ourselves into a culture where we’re smaller than our potential—to get along, to survive. So I resist capturing the essence of Future of the Body or of peak mystical experience with phrases like flow or in the zone. These are all nice ways to talk about it but it’s a little too narrow for me. We do have to be big enough to meet the world that’s trying to emerge. Most of life is hiding in plain sight. That’s the most radical statement. We can walk through a doorway and get unstuck, like in Alice in Wonderland, and find out, “My God, what have I been missing?”

You and your wife, Dulce, have a long track record of working to improve relations with Russia. Can you explain this initiative?

The idea has been to create citizen diplomacy. We call it Track Two Diplomacy, and you can see the website that explains this [Trackii. com]. It is a non-governmental approach to improving relations between nations in conflict through informal, private-sector collaboration. It started for me in the late ‘60s when early teachers started to come from Europe to Esalen and told us about the action deep inside the old communist regime. I started writing letters to Russia in Then there was a popular book called Psychic Discoveries Behind the Iron Curtain that documented much of the same stuff as the Human Potential Movement—describing “hidden human reserves.”

In 1971 I went there and met the characters described in this book. Among others there was a famous telepathist, Karl Nikolaiev, whom I watched in action and it was real telepathy, unbelievable! There is no way there was any magic or cheating. And others like Jim Hickman and Stanley Krippner went over. So we bonded with healers, shamans, people doing paranormal research, spiritual healing, and a little bit in sport already, interestingly. And our interest grew and grew. At the same time the fear of nuclear confrontation was growing.

In 1980 America boycotted the Moscow Olympics but we were encouraged by the very guy—we happened to know him—in the Security Council who was running the boycott to attend a separate conference that was taking place during the Olympics. So it was not exactly heroic on our part because here’s the guy running the boycott who said “Go.” Anyway we got instant entree into these two separate worlds. One was the Bohemian underground and the other was straight into the Central Committee of the Soviet Union, and the Politburo.

We deliberately did not associate with official dissidents like Sakharov and Solzhenitsyn because we knew if we played that game we couldn’t go in as far. Instead we became friends with people like Valentin Berezhkov who had been Stalin’s interpreter and Vladimir Posner, Russia’s famous journalist, the equivalent of Charlie Rose and Walter Cronkite. After nearly forty years Vladimir is like a brother to me; he wants his ashes scattered at Esalen. So through these friendships and dialogues and the implicit aim of helping end the Cold War we just lit up. Dulce really lit up! She, more than anyone else, has held this initiative together.

We’ve brokered hundreds of exchanges. One was connecting the Russian writer’s union—that’s how they control you over there—and getting them into the International Pen Club, which is the international association against censorship. Dulce carried a lot of the water on that one, right at the hinge before Gorbachev and Glasnost, working with people like Norman Mailer, Kurt Vonnegut, Susan Sontag, and John Irving.

Another thing we did was with Rusty Schweickart, the Apollo 9 astronaut, where we helped form an alliance between cosmonauts and astronauts called the International Association of Space Explorers. That group has been meeting ‘til this day. That was initially brokered by Esalen. And that in turn gave birth to another organization—I can see their office across the street [points to the Mill Valley offices of the B612 Foundation]. They are leading the attempt to watch and deflect asteroids that could hit Earth.

Wow! And didn’t you bring Boris Yeltsin to America for the first time?

Yes. There were young people around Yeltsin who wanted us to bring him, so we did. He didn’t come to Esalen but we paid for the trip and Jim Garrison, who was the director of our project then, squired him around. Literally, in a Houston supermarket [pause] Yeltsin had a conversion experience [long pause]. I mean he just blew up [pause]! That he’d been lied to all his life by the Communist bosses!

The difference between Yeltsin and Gorbachev was that Gorbachev thought communism could be fixed. Gorbachev was the primary one responsible, with Reagan, for ending the Cold War but Yeltsin was responsible for dumping communism and then splitting up the Soviet Union into the 15 republics. So it took the one-two punch to accomplish all of that but we paid for and brokered that trip which led to Yeltsin’s rejection of communism.

Unfortunately our foreign policy establishment has made mistake after mistake since Yeltsin came and the Americans helped to dismantle the old system. Since Nature abhors a vacuum, in came these tough guys and oligarchs and then it got out of control. Putin brought in law and order and helped open a way for Russia to prosper in large part by suppressing the various ethnic mafias that emerged—violent mafias that made the Sicilian mafia look like a bunch of pussies [laughs]!

What do you make of USA-Russian relations in this Trump era?

Not good [sighs]. And that’s not primarily Trump’s fault. His reflexes are correct in wanting to reach out to Putin but that just riles up our MSNBC and CNN on the left, who are justified in criticizing his often clumsy and crazy-seeming Russian policy. Plus the collusion or quasi-collusion involved in his election—that’s not helpful. But meanwhile some of America’s best diplomats and scholars with whom we are affiliated are working to improve these relationships. It’s a work in progress. The world today is getting more accident-prone, particularly because Russia and America between them own 92% of all the nuclear weapons on Earth. One bomb could take out the Bay Area—so for that reason alone…

What ticks you off?

Tyranny. In all its forms. And this willingness to come in and to take over someone else’s good work. I’ve experienced it at Esalen. Somebody will come in and say they know better even though they don’t even know what you’re doing. That angers me as does this outrageous behavior of Donald Trump. He has the right impulse with Russia and Kim Jong Un—mafia chiefs know how to deal with mafia chiefs. But his bullying, his incivility, his swagger through the world—it can’t go on much longer. Something’s got to give.

I do have a strong archetype in a Jungian sense for freedom—we have to keep winning our freedom. My experience of people is that love and safety come easier for most people than freedom. Unfortunately this leads to a compliance with bad things in the world—and a slowness to take a stand and go for the good. We need to find good stories for ourselves. That’s why I believe in evolutionary panentheism—that the Divine is immanent and is disclosing itself in the course of time. We’re here to enjoy it and foster it. And at times we have to fight for it.

What is the Center for Theory and Research at Esalen?

This was a part of Esalen I organized as a way to nurture the kinds of programs we do that are not open to the public. You could call it our research and development wing. We sponsor research initiatives and hold invitational conferences around the world. It started in 1963 to mark it off as a “safe space” because organizations can consume their young. Organizations get muscle-bound and the worst ones become cults. In this sense we’re like a college where the trustees and the administration cannot go in and tell the professors how to do their research.

The empirical exploration of “evidence for life after death” is one example. We’ve had arguably the smartest group of people working on this for 15 years because it’s not going to happen at Stanford or Harvard but they would come from places like Stanford and Harvard.

What are other topics?

The Russian-American relations work we discussed has been going on for decades but it has also been going on with the Middle East between Palestinians and Israelis. We’ve done a lot to promote the scientific study of Somatics. Don Johnson for years brought leading Somatics teachers together with scientists to look at what’s really happening in practices such as Rolfing, Feldenkrais work, and sensory awareness training. And just as we’ve been involved with psychology, philosophy, and religion, Esalen has also always been at the cutting edge of ecological study with a big influence of the Rudolph Steiner-Alan Chadwick-type practices like organic gardening, biodynamics, permaculture. All these kinds of ideas and modalities have been featured for decades in Common Ground magazine. To some extent we’ve grown up side by side.

Indeed [laughs]. Are you ever starstruck by the high-profile celebrities with whom you interface?

I am often in awe of people’s accomplishments but the star-struck phenomenon wore off in the first years. That said I could barely speak when I first met Aldous Huxley [laughs].

Do you miss Dick Price? He died while hiking in 1985.

Of course I miss him. I will always be grateful for his comradeship in the early years. He had fantastic resilience and humor. He used to describe thorny situations by saying, “This is hopeless [pause], but it’s not serious.” You just had to laugh!

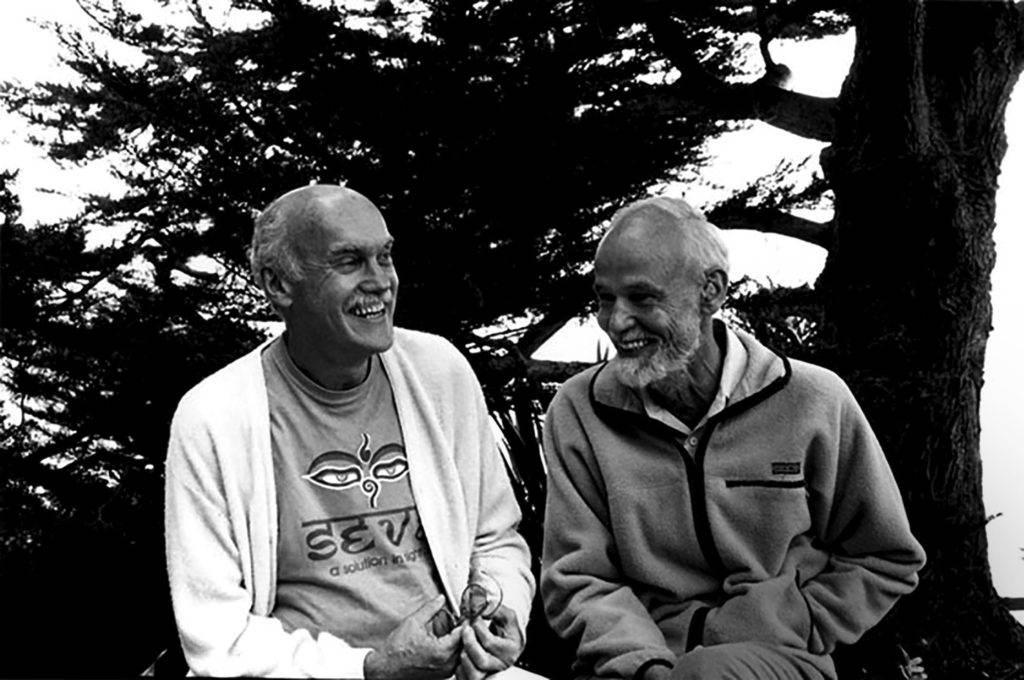

I know you miss your dear friend George Leonard.

Oh yes. He was the West Coast editor of Look magazine and was involved with the Civil Rights movement and various other great occasions, both as a change agent and eminent journalist. More than anyone he helped steer us through the media onslaught we endured in the late ’60s and ’70s. He was an Esalen officer and board member for decades, alerting us to countless complexities of American politics and culture. He and I started the Integral Transformative Practice, in which I’m still involved. Yes, I miss him; we were like brothers.

It just seems you’ve every gift—brainpower, athleticism, connections, luck. You’re hardwired with spiritual insight. How do you factor providence in your life or the notion that you’re reincarnated to serve a mission?

[speaking slowly] Providence—it’s a hell of a word. Basically I believe in providence. Reincarnation—I am open to it but I have no memory of a past life. I’m a lucky guy so at times I am tempted to believe in reincarnation. How did I end up with that property at that point in life with that deep, powerful calling? By the time I was 11 I was forming a worldview and by 15 it was pretty well developed. When I walked into Spiegelberg’s class it just lined up. Yet so many people have walked into his classes but nothing like that happened.

When Esalen started I kept a journal of coincidences. I had just bought a dozen copies of Abe Maslow’s Psychology of Being—mind you we hadn’t even started Esalen yet—when Abe Maslow of all people drives into the place—looking for a room! What do you make of that? I’ve often thought, “Who the hell’s running the show here?” There certainly is some Esalen dharma and hey, I am open to all the graces and notions of reincarnation. I do have a firm conviction that Atman is Brahman, that deep down we are one with the All.

And now that I am about 88 I think a lot about life after death and The Tibetan Book of the Dead. How do you die? How do you cross over? All that is up for grabs now—and what will happen to Dulce and Mac?

Can you end with a message for Common Ground readers, many of whom know Esalen and many of whom do not?

Well, I can say to everybody, “Really embrace your dharma.” If you don’t know what your dharma is, call for it. Call to God for it. Call to your best friends for it. And then go for it. Life will reward you. That’s my main message.

Rob Sidon is publisher and editor in chief of Common Ground.