A Spiritual Memoir

The practice of medicine, which I began after moving from India to the United States in 1971, is an odd opening to God. But finding out what’s wrong with a patient comes close to being a spiritual investigation, improbable as this may sound. Unless someone is wheeled into the emergency room with a broken leg or gunshot wound—both were common occurrences in the New Jersey hospital that was my first exposure to American medicine—the doctor begins by asking “What’s wrong?” The patient then gives a subjective account of his aches, pains, and specific discomfort. This account is likely to be filtered through distortions such as high anxiety, distrust of medicine, or in my case back then, skepticism that a young M.D. from India really knew anything. (“Can I see a real doctor?” was written on the faces of many patients in an era when the Vietnam War had created a doctor shortage, leading to an influx of foreign-born and foreign-trained physicians.)

Although we all visit the doctor routinely to find out what’s wrong with us, certain situations depend almost entirely upon subject-reporting. Pain is the most obvious example. There is no objective measure for pain, no reliable scale like the level of liver enzymes or hormones in the blood. “It hurts” is the only standard, and the patient’s description of how much it hurts and where cannot be refuted. Depression and anxiety are also heavily dependent on subject-reporting. Even though brain scans are beginning to offer a hint at objective measurement, the general conclusion seems to be that every depressed patient is a unique case.

Diagnosis, then, implies a subtle struggle between what the patient reports and what the physician concludes to be true. The unspoken object of this contest, from the doctor’s viewpoint, is to reduce subjectivity as much as possible so that medical science can get at the facts and nothing but the facts. It is absolutely necessary for subjectivity not to rule the practice of medicine, while on the other hand pure objectivity is a chimera.

My father had a long career as an Indian Army physician, a cardiologist, and it was a point of pride with him to reject Ayurveda, the centuries-old indigenous medicine of India, in favor of “real medicine,” meaning the Western science-based variety. So a high respect for science was ingrained in me from my childhood onward, even though my grandmother was a staunch believer in Ayurvedic remedies, or folk remedies as my father would have labeled them. I felt no qualms about this division in the family, and after a certain age, perhaps 12 or 13, I understood why my father was also a nonbeliever in God while all the women in the family, including my mother, were strongly devout.

Unless you have respect for subject-reported facts, religion is nearly impossible to credit. There are no facts about God—none that rise to the level of science, that is. Saint Paul may have been struck by divine light on the road to Damascus, but a traveler going in the opposite direction might simply have seen a man fall down on the side of the road. I recently asked a woman why she had become a deeply convinced convert to Roman Catholicism, and she replied, “Jesus was either a deluded psychotic or the Son of God, and I’m sure he wasn’t crazy.” She hadn’t considered another, obvious possibility: Jesus could have been ordinarily sane but very convinced by his subjective experiences. So far as I could see in my early life, which was spent as a scientific atheist, all religions were founded on subjective and therefore unreliable experiences.

Yet I had an uncle whose hobby, as it were, consisted of visiting saints on a regular basis. “Saint” is a very general term in common Indian usage, denoting a holy man, swami, yogi, mystic, or enlightened master. No official body confers the title, and people regularly sit in the presence of saints in order to get a blessing, or Darshan. I went with my uncle as a fascinated youngster on various Darshan jaunts, and I was impressed that being in the presence of a saint made me feel peaceful and quiet inside. There was sometimes a sense of bliss, or Ananda, that is considered a classic sign of true Darshan. I later realized that for my uncle, this was actually a serious enterprise, because he had adopted the belief, which goes back to before written history, that setting eyes on the enlightened ensures that you yourself will one day be enlightened (in fact, the Sanskrit root of Darshan is “to see”).

This prelude brings me to the point of my argument about God today, and specifically the immanent God. The crisis of faith that surrounds us and so troubles churchmen and believers of every stripe can be solved only one way, by making God necessary. Unless God enters into daily decisions and, furthermore, brings about better results than doing without God, the divine will be at most an add-on to modern life. Any version of God that is personal, incidental, occasional, fickle, or unknowable cannot be a God I’d call necessary. Oxygen is necessary, along with food and shelter; money is necessary for all but the smallest fraction of society; and to the list could be added love and happiness, although those qualities are done without by untold millions of people.

In order to make God necessary, there is a journey from belief to faith and from faith to knowledge. One lesson from my medical practice, reinforced by science in general, is that subjectivity isn’t good enough. There must be objective conclusions and, still better, practical solutions. Looking upon the seemingly superhuman calm with which Socrates faced death, Nietzsche thought he was glad to be cured of the disease of life. As rebellious as that sounds, the Buddha would have agreed, in a different way, that life’s inevitable baggage of pain and suffering must be approached with radical surgery—the necessary treatment was ego death, the end of personal attachment to the cycle of pleasure and pain.

Lacking a rebellious streak, I’ve concluded that the point of spirituality is to deliver a kind of medicine to the soul, a recovery program that invests life with “light.” This word has countless meanings in the world’s spiritual traditions, but here my use is simply the light of knowledge—knowing what is real and disposing of what is unreal. If God cannot pass the test of knowledge, the spiritual journey remains incomplete or even aborted.

Belief is the first step, which is different from faith. Belief is more tenuous; it involves a willingness to believe that God is a possibility. A confirmed atheist won’t accept belief as a first step, and countless modern people are satisfied enough with secularism that for all practical purposes they are practicing atheists. But if belief is adopted, a person starts to examine if something real is the object of belief. Children believe in fairytales, but to carry this belief into adulthood implies a kind of self-indulgence, an enjoyment in fooling oneself on purpose. Bible stories are like fairytales in the way they defy ordinary reality, and as children nothing is more captivating than miracles. But holding on to Bible stories as the basis of belief in God strikes me as a sort of self-indulgence, too, bringing the same pleasure in fooling oneself. Without holding a miracle up to the same validation as a blood test, we ignore the demands of reality.

But validating God is a long time coming, I realize, and this requires the second stage on the journey, faith. Faith is more convinced than belief. It is upheld by actual personal experience of some kind that points toward the divine. To my mind, knowledge of God isn’t privileged over other kinds of knowledge. A physical brain is required, along with measurable activity in various regions of the brain that correlate with what a person is experiencing subjectively. To see angels requires the same visual cortex as seeing a cow. There’s a trap here, however, that needs to be avoided.

The fact that the brain is active during spiritual experiences isn’t the same as saying that the brain creates those experiences. It only processes them. In Tibetan Buddhist monks who have meditated on compassion for years, the prefrontal cortex lights up with extraordinary intensity on an fMRI. Certain frequencies of brain waves are also greatly intensified. Looking at this evidence, some have argued that neuroscience has validated that spiritual experience is real. I think that’s a wrong conclusion, because nothing stronger than inference is involved. On an fMRI a neuroscientist sees only neural correlates, the physical fingerprints of something that isn’t actually measurable. In fact, not just spiritual experience but all experience isn’t captured through brain activity, any more than knowing the workings of a radio tells you how a Mozart symphony being broadcast through the radio was created. Hooking Shakespeare up with electrodes while he writes Hamlet won’t reveal the first line, or even syllable, of the play, much less its meaning.

The whole point of spiritual experience is its profound meaning for the individual, which can be life-changing. If someone leaves her everyday existence to become a secluded Carmelite nun, it’s folly to say “her brain made her do it.” Her experience, filtered through her mental evaluation of it, made her do it. I would say that everyday life, in fact, is littered with clues and hints of spiritual experience. These passing moments take on a flavor everyone can identify with, even the most convinced atheist. Let me offer a partial list, which consists of moments when you or I feel:

» Safe and protected

» Wanted

» Loved

» As if we belong

» As if our lives are embedded in a larger design\

» As if the body is light and action is effortless

» Upheld by unseen forces

» Unusually fortunate or lucky

» Touched by fate

» Inspired

» Infused with light, or actually able to see a faint light around someone else

» Held in the presence of the divine

» Spoken to by our soul

» Certain that a deep wish or dream is coming true

» Certain that a physical illness will be healed

» At ease with death and dying.

Only a fraction of the items on this list conform to the conventional notion of a religious experience (although pollsters have found that ordinary people, up to a majority, report seeing an aura of light around someone else at least once in their lives, and hospice caregivers routinely see something like the soul leaving the body at the moment of death. These are phenomena difficult to talk about, even embarrassing, in the context of secular society). It takes a degree of faith in yourself to acknowledge these experiences and even more faith to follow them up. I’d call lack of follow-up he real loss of faith, because all too often the most extraordinary experiences pass through our lives momentarily and then are lost in the welter of daily existence.

Faith in your own experience is crucial. Once you notice that you’ve had a meaningful experience of the kind I’ve listed, you must give it significance. This is a harder step for most people, because they have been conditioned from childhood to identify with secondhand labels. In my case, for example, the labels include Indian, male, late middle age, doctor, married, well-to-do, and so on. As we accumulate labels, hoping to be known by positive tags rather than negative ones—I’ve had more than my share of the latter—we develop an ongoing story about who we are. This story is almost entirely externalized, because that’s how labels work. Insidiously, we start to prefer labels over experience, especially when an experience would set us apart as different. “I am an endocrinologist” was a prestige tag for me in my profession. It took a bit of daring to substitute “I am a mind-body doctor” or “I am a meditator”—those tags were quite suspect in the 1980s. What if I became known without tags, both to others and to myself? “I feel like a child of the universe” or “I was touched by God” aren’t safe ways to identify yourself.

So in the stage of faith, you must shift your allegiance to what you actually experience, which leads to a new, more authentic story about who you are and where you are headed. Much of the panic among professional religionists today can be traced to the collapse of traditional stories, stories of saints, miracle workers, the humbly devout, trials of faith, and rewards and punishments from God. Nietzsche notoriously thought that religious stories were power plays, methods by which a priest caste controlled believers. I’m willing to shrug off such accusations, because in reality, to live by any secondhand story keeps us from true knowledge. To accept conventional wisdom is the surest way to remain unwise.

Once you’ve given significance to your inner experience, more experiences start to arrive. You’ve turned on the tap. Everyone, as it happens, already entices phenomena to appear. If you walk around with a chip on your shoulder, there will always be more reasons to pick a fight. If you are an ingrained optimist, your day will be filled with things to be optimistic over. In other words, each of us creates personal reality through a feedback loop with the larger reality. Being infinite, the larger reality—known in Sanskrit as Brahman—can supply endless evidence that your personal story is valid. At some point it’s important to believe this; otherwise, the alternative is to lead a meaningless life, which no one can tolerate. Then comes a change. The things you believe in start to become less personal, less about “I, me, and mine.” Spirituality becomes more and more selfless.

Being practical modern people, we want a payoff for the time and effort we invest in things, and selfless spirituality has no obvious payoff. It would shock most seekers to hear that finding God or enlightenment doesn’t make you a better person or smarter, richer, more respected—it doesn’t make you more of anything. Wanting more is an ego game. It is intertwined with the ego’s innate insecurity, which tries to find security by acquiring more of the good things in life and reducing more of the painful things. Rupert Spira, an inspired speaker on these matters, was once contemplating the question of the afterlife. “The ego wants to survive after death,” Spira remarked, “so that it can come back and tell everyone about it.” What would impress your friends more than telling them you just got back from a trip to Heaven? It beats the French Riviera.

Faith on its own is insufficient; it sustains us in a mixture of truth and illusion. Our minds, our desires, our wishes, fears, and dreams, lead us on, but there is always nagging uncertainty. Some things are convincing but illusory, like the ego’s desire to be totally pleasured at every moment or to be liked by everyone. This jumble of illusion and reality all has to be sorted out. I associate the ripening stage of faith with emotional maturity, or what might be called “building a self.” The essence of making God necessary is coming to grips with reality. A strong sense of self is required, never more so than when you realize that the self must be jettisoned. At that point, founded on your inner experiences, you are ready for the third and last stage, which is true knowledge.

True knowledge doesn’t come with a signpost pointing to God. Instead, what you start knowing is the nature of existence. The only two things any of us actually knows with total certainty is that we exist and that we are aware of existing. Ironically, these are the two things everyone takes for granted, whether they call themselves atheists or believers. “I am” needs no follow-up. As soon as you say, “I am X,” the X dominates your thought. “I am Deepak, an Indian male, a doctor, etc.” forms a train of thought that leads, step by step, away from the simplicity of “I am.” There’s good reason for why Moses heard Jehovah say “I am that I am” from the burning bush. It’s the one true thing that connects the human and the divine. “I am” is the beginning and end of wisdom.

This needs explaining, naturally. If you take the physical world as a given, existence is empty and inert. It’s empty in that life won’t matter unless it gets filled with countless experiences that arrive on a conveyor belt from birth to death. Existence as nothing but a physical fact is inert because until the mind enlivens it, nothing “out there” matters. Hamlet’s “To be or not to be, that is the question” actually misses the point. To be is inevitable, beyond choosing. The real question is what existence means. This becomes an urgent question once the demands of “I, me, and mine” are exhausted or abandoned. A quote whose source I forget comes to mind: As long as you have a personal stake in the world, enlightenment is impossible. Or to make this truth more comfortable for Westerners who are suspicious of enlightenment, as long as you have a personal stake in the world, you won’t know who you really are.

I’ve been asking for the reader’s indulgence by not bringing up the immanent God, which is the putative subject here. But now we are close. If existence isn’t fated to be empty and inert, it must be something else, replete and alive. The fullness of reality and the source of all life is God. When you come to the stage where you are urgently interested in existence, it turns out that awareness cannot be left out. To exist and to be aware that you exist go hand in hand; ultimately they are one. In the ancient Vedic tradition of India, this seamless unity, this one thing upon which all things are founded, was simply called “That.” Two enlightened people could meet on the street with totally different backgrounds and completely divergent opinions about everything. But both would agree to the statement, “I am That, you are That, and all this is That.”

“That” is too unspecific for theologians, and labels have been applied, such as Brahman, vidya, mahavakya, and so on, in order to find the right label. But this effort, along with the theology it is part of, runs against the intention of “That,” which is to point beyond all language to the source of everything. God as origin belongs in every religion, it goes without saying. But origin without God is much trickier. The one great advantage of the Indian tradition, as I view it, lies in getting at the source without resorting to anything beyond existence itself. If God isn’t existence, then the search for God will only lead into deeper illusion. That’s the bottom line of “I am That.”

In the final stage of the spiritual journey, to be is enough. Being is awareness, and there is no getting beyond awareness. What we are not aware of might as well not exist. A current fashion among physicists is to posit an infinite number of possible universes that comprise the so-called “multiverse.” These alternate universes are necessary for cosmological reasons. For example, they get us past the nonsensical question, “What came before time began?” By general agreement, time and space, along with matter and energy, emerged at the instant of the Big Bang. Since the human brain is a product of time, space, matter, and energy, the pre-created state of the universe is impenetrable. But mathematical conjectures can be applied to a supposed pre-creation, and using one set of complex mathematical formulas allows proponents of the multiverse to imagine a cosmic casino where trillions of universes bubble up at random. One of these bubbles is the Big Bang, which completely at random produced a universe that fostered human life. Thus “our” universe has time and space in it, along with the force of evolution, making Homo sapiens a winner at the cosmic casino.

Theology couldn’t be more fanciful or divorced from reality than this, and it’s only an historical happenstance that makes us speak of the multiverse as more respectable than speaking of God as source and origin. “That” gets us past all historical happenstances. Neither an age of faith nor an age of science matters. In any age, the individual can find the truth simply by paying attention to the undeniable fact that existence and awareness are intertwined. At any given moment, someone in the world is amazed to find that the God experience is real. Wonder and certainty still dawn at these moments, whenever they arise. I keep at hand a passage from Thoreau’s Walden, where he speaks of “the solitary hired man on a farm in the outskirts of Concord, who has had his second birth.” Like us, Thoreau wonders if someone’s testimony about having a “peculiar religious experience” is valid. In answer, he looks across the span of centuries: “Zoroaster, thousands of years ago, travelled the same road and had the same experience, but he, being wise, knew it to be universal.”

If you find yourself suddenly infused with an experience you cannot explain, Thoreau says, just be aware that you are not alone. Your awakening is woven into the great tradition. “Humbly commune with Zoroaster then, and, through the liberalizing influence of all the worthies, with Jesus Christ himself, let ‘our church’ go by the board.”

Skeptics turn this advice on its head. The fact that God has been experienced over the ages only goes to show that religion is a primitive holdover, a mental relic that we should train our brains to reject. But all attempts to clarify matters—to say, once and for all, that God is absolutely real or absolutely unreal—continue to fail. The muddle persists, and we all have felt the impact of confusion and doubt. What this tells me, however, is that it’s impossible to stand aside from experience when we come to the source. Just as time, space, matter, and energy emerge from a pre-created domain that is timeless and without dimensions, the source of awareness is inconceivable. “That” is ground zero, the womb of reality. There is no more language, or even thought. As the ancient Indian rishis declared, “Those who know it speak of it not. Those who speak of it know it not.”

It’s only sensible to ask if such knowing, being impossible to talk about, is actually real. This has been a vexing dilemma that gave rise to two huge topics in philosophy: ontology (the study of being) and epistemology (the study of how we know things). Both topics are gnarly and entangled, and Indian philosophy isn’t immune from that. But we can cut the Gordian knot with another expression from the ancient seers: This isn’t knowledge you acquire. It is knowledge you become. God, like the universe and reality itself, is participatory. There is no other choice, since existence is always on the move, which is why I’m fond of saying that God is a verb, not a noun.

If the argument feels like it’s getting opaque, I can offer an analogy that helped me when I first heard it. Imagine that your mind is like a river. On the surface a river is filled with activity in eddies and waves. As you go deeper, the waves subside into a steady current. Deeper still the current slows down, and at the very bottom of the river, there is no current at all as water settles into the underlying river bed. Just as we can trace a river from its most agitated state to a level of complete stillness, the mind can follow itself from the stream of consciousness to deeper levels until it encounters its source in silent awareness. The entire journey is accomplished within awareness; the beginning, middle, and end are all conscious.

The practical result of this dive into awareness is not abstract knowledge. Reality is different in different states of consciousness—another maxim from the ancient rishis. Therefore, God isn’t merely process but transformation. In this book the authors were assigned the topic of “the immanent God,” which acquires its importance as a kind of rescue mission. As the transcendent God loses significance in the modern world, we must turn to immanence—“God in us” or “God in everything”—to justify the divine. I have to agree, but with the proviso that transcendence and immanence aren’t relevant distinctions in the end. We don’t say, “Existence is way up there, beyond the clouds. Have faith and you will find that existence is down here, too.” Likewise, if God is existence, being “up there” or “down here” has no meaning.

I could give a preview of coming attractions by holding out what higher states of consciousness must be like. The Indian tradition has thousands of pages on the subject. But the simple truth is that transformation never ends, and states of consciousness lead to realities that must be experienced directly. The Vedas sound reassuring when they say “You are the universe,” a kind of ultimate validation of what it means to be human. Like everyone, I’ve spent my life searching for validation. I try in all frankness not to describe experiences I haven’t had myself. The curious reader can infer throughout this chapter that everything being described has happened to me.

I am the union of two parents, in a sense, unwilling to rely on science or faith alone but equally unwilling to let go of either strand. It’s a peculiarity in human beings that we never settle on a fixed identity, the way a tiger has tigerness and perhaps an angel has angelness. In the evolutionary scheme, our specific mutation is to embody mutability. I feel that personally every day, and if you ask me “Who are you?” I don’t resort to memory, family, labels, and other remnants of selves that have drifted in and out of the picture since I was born. All statements of “I am X” fall short—even “I am -God”—to explain what is real at this very moment. Existence is on the move, and the only reliable guide into the unknown is reality itself.

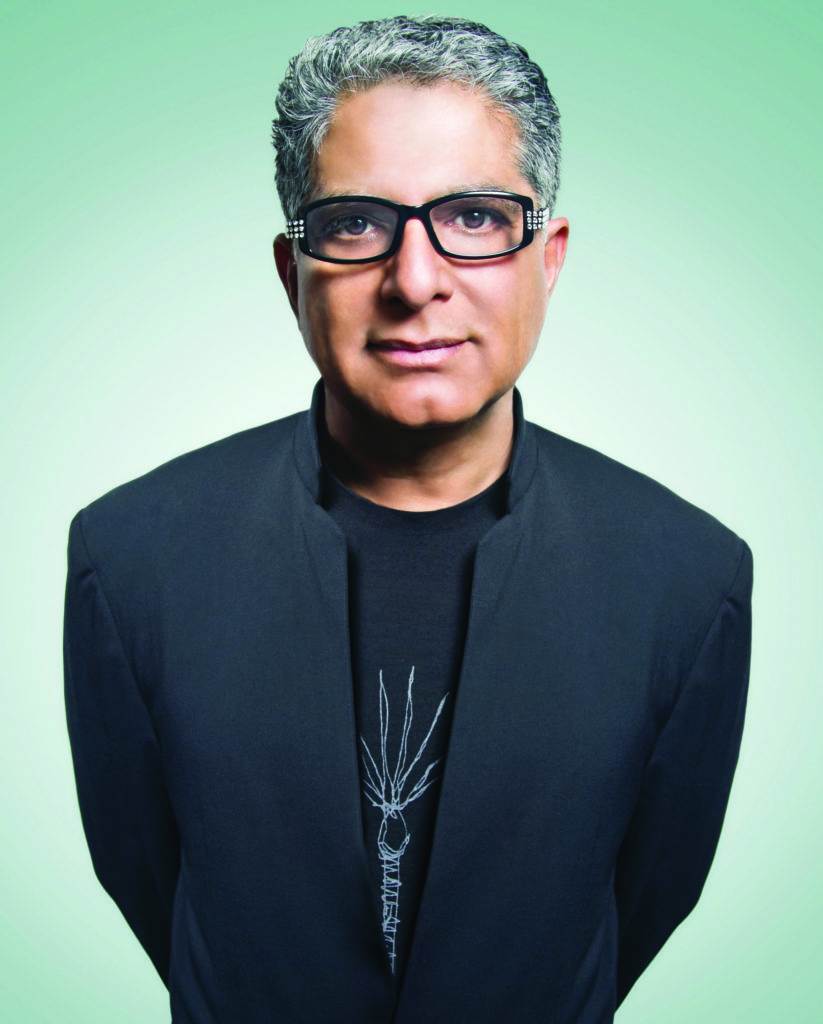

Deepak Chopra is a prominent Indian-born American bestselling author, public speaker, and alternative medicine advocate who participates this month at Bhaktifest in Joshua Tree and in October will appear at the Science and Nonduality Conference in San Jose. This essay is included with kind permission from How I Found God in Everyone and Everywhere: An Anthology of Spiritual Memoirs by Andrew M. Davis and Philip Clayton, courtesy of Monkfish Book Publishing. MonkfishPublishing.com