A Journey from Food to Psychedelics to the Nature of Consciousness

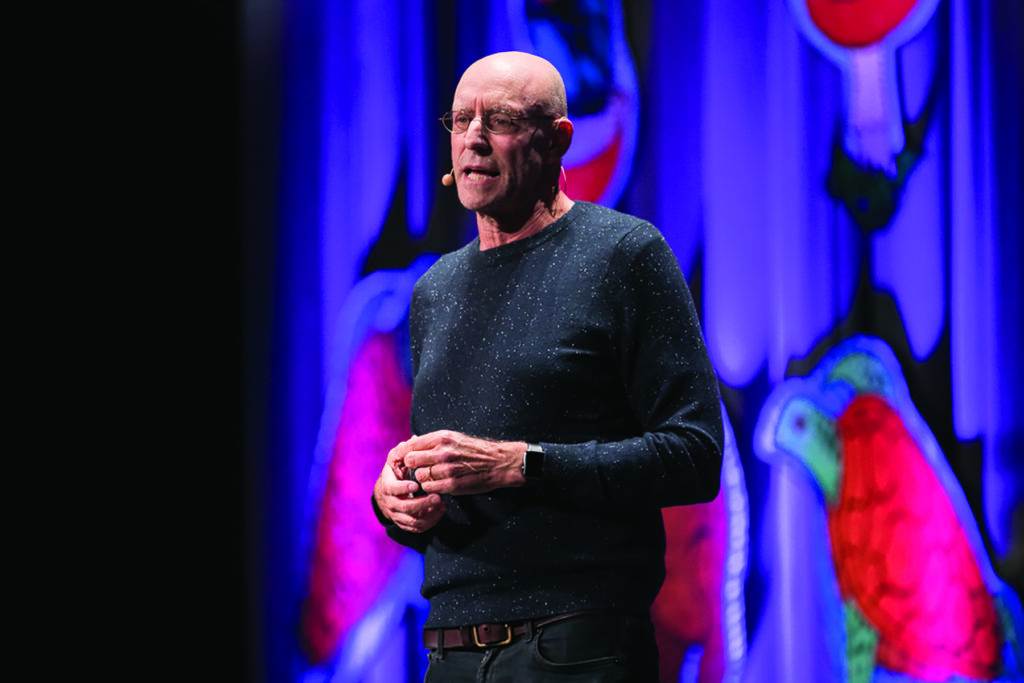

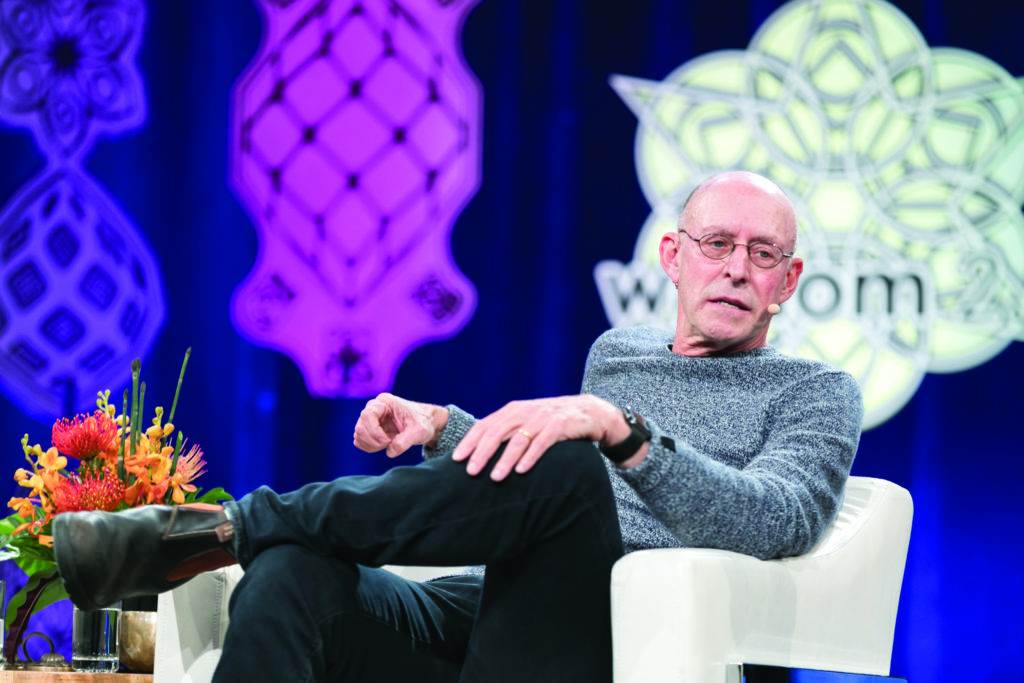

Michael Pollan loves the written word. He worked as an editor at Harper’s Magazine while writing his first book, Second Nature, on nights and weekends. While writing his second book, A Place of My Own, he took the plunge to become a full-time writer. His big successes came with Botany of Desire, The Omnivore’s Dilemma, and In Defense of Food, which all became bestsellers and established him as a leading voice in the natural foods movement. The winner of numerous writing awards, Pollan is a chaired professor of journalism at Harvard University and the University of California at Berkeley.

In 2018, with his latest work, the well-researched How to Change Your Mind: What the New Science of Psychedelics Teaches Us About Consciousness, Dying, Addiction, Depression, and Transcendence, he again quickly captured the international spotlight—this time by urging a medical and cultural reassessment of psychedelics, which had been categorically vilified and criminalized as part of the government’s war on drugs.

Pollan grew up Jewish but took little to no interest in spirituality, preferring to appreciate life from an empirical scientific perspective. Pollan is a busy man who lives in the Bay Area, where we caught up with him to discuss a myriad of topics ranging from the art of teaching journalism to how his recent psychedelic experiences helped him transcend his limited ego and find deeper connection. We discussed how psychedelics changed his own mind, notably by improving his capacity to stay present during his father’s passing—as well as broader mysteries such as “What is the nature of consciousness?”

Common Ground: Change Your Mind has gotten such a positive reception, taking you from being a natural foods superstar to a superstar in the psychedelic movement. How has it affected you personally?

Michael Pollan: It’s been a huge surprise to me—that the general reader was ready for a book on psychedelics. There had not been one, or not in a long time. Most books on psychedelics are written for people in the community by people in the community. I tend to write as Everyman and as an outsider entering into a subculture rather than as a member of that culture. I was surprised the book was embraced by as many people as it was, both inside and outside that culture.

Switching from being the food guy to the psychedelic guy has been challenging in some ways. Being the food guy’s easier. The questions people ask are not nearly as searching or personal or poignant. People ask “Should I eat this? Is gluten evil? Is caffeine evil?” Easy questions to answer. The psychedelic guy gets quickly in touch with the depth of human suffering around mental illness. I have had hundreds of requests asking if I can make a referral. People will tell me about their suicidal son or their alcoholic father. I realize the book has fanned the flames of hope for a lot of people but I can’t deliver on it. I can’t make referrals and never do. It’s too dangerous for everybody involved because these guides are underground. I have learned something about where the public is, which is lonely, disconnected, addicted, depressed, anxious. It’s been moving to realize the depth of the problem.

What is breaking open in the zeitgeist?

The response to the book has helped me understand that we need help. The tools mental health care has are inadequate. The big surprise has been to see how much work is needed to help people with mental suffering. If [these psychedelic medicines] can realize the promise they’ve exhibited in early trials, it’s going to be a huge deal. It’s not a foregone conclusion but these could just be the kinds of tools many people are looking for. That’s one thing.

Also the drug war is losing steam. It’s becoming widely recognized that it’s been a failure resulting in throwing lots of people, especially people of color, in jail for little reason. The government doesn’t need it. I’ve always thought the drug war was about how the government accrues power. Once you had a war on terror post-9/11, you didn’t need drugs for excuses to curb civil liberties and assert government power. We’re seeing drug problems apart from illicit drugs. The opiate epidemic was essentially started by pharmaceutical companies, not by El Chapo or anybody like that. Our understanding of drugs is shifting. People are willing to look at them one by one and not lump them together as this great evil.

In fact people get in trouble on legal drugs and sometimes thrive on illegal drugs. In the zeitgeist we’ve decriminalized or legalized marijuana recreationally in ten states and many more for medical. That has changed the image of all illicit drugs.

A collective shift in consciousness?

People are looking for a change in consciousness. You have Boomers who first experimented with psychedelics now reaching a second chapter where they’ve become relevant again. Boomers are getting older, facing cancer diagnoses and their own mortality. With their kids out of the house you’re seeing Boomers revisiting psychedelics and you’re seeing Millennials discovering them for the first time.

Then there’s the hole in the doughnut of parents with kids at home. I find them most resistant to anything positive I have to say about psychedelics—because it’s complicated. There are always some mothers in the room whose ears are closed whom I can feel are clenching. They can’t listen—until I talk about the risks and the problems—and there are real problems attached to psychedelics.

Aside from that group I’ve found an openness on the part of people in their 80s who are curious and have approached me about access to psilocybin or underground guiding. Even my mother-in-law, who’s 92, inquired. But I make no referrals and supply no medicine.

More than 50 years ago Timothy Leary was the Pied Piper goading the culture to turn on. He’s been criticized for going too far, too fast. Do you fear being compared to Leary for these reasons?

No. I think you’re the first person to compare me to Timothy Leary. I have been criticized for being too positive in my portrayal of psychedelics. Of course if you’ve had the experiences you’re bound to betray some exuberance and excitement about the potential. I’ve tried to temper that by describing terrifying trips and talking about the real psychological risks. People do get into trouble! I have never suggested they’re for everybody or to “turn on, tune in, and drop out.” I’ve also never provided medicines. Those are important distinctions. I may have the cultural ear on the subject, as he did, but have the advantage of learning from his mistakes, which were considerable.

He made a contribution, without question. He created a world safe for this new generation of research and for this renaissance by turning on so many people. He also contributed to the backlash. I’m hoping not to do that by taking pains not to say the kinds of things that antagonize people.

Let’s talk about risks. My take is—“What goes up must come down.” How do you caution people?

I was a very reluctant psychonaut. As a science journalist I felt it was incumbenton me to study the risks. A lot of people told me about the benefits—but what were the risks? I looked closely and was surprised to find that the physiological risks were remarkably slight. These are essentially not toxic substances. I’m talking about the classic psychedelics, DMT, LSD, psilocybin. They’re also non-addictive. They’re not really drugs of abuse in that they’re not habit-forming. In the case of cocaine or heroin the lab animals will self-administer with the lever contraption until they die or are addicted. In the case of LSD they’ll do it once and never again—not habit-forming—which is a significant worry about a drug.

The problems are more practical and psychological. The practical problem is that people sometimes do stupid things. Their judgment is disabled and their physical ability is sometimes disabled. People walk into traffic and fall off buildings. That can happen, especially in an unsupervised setting. And then psychologically—Johns Hopkins did a bad trip survey of thousands of people about their most challenging experience and about eight percent of them sought psychiatric help over the course of the next year. That suggests people had gotten into some serious psychological trouble, and that’s worth being aware of. Again, these are not supervised trips and that does change things.

There are a certain number of people who have psychotic breaks on this. They may have been schizophrenic but not yet manifested and the drugs tipped them over. It’s worth saying that marijuana can do that too, and alcohol. A parental divorce can do it. A lot of trauma can initiate schizophrenia in people who are genetically inclined.

It’s rare but some people experience recurrent imagery long after they’ve taken the psychedelic, the acid flashback. Basically people at risk for serious mental illness should stay away but those risks can be mitigated by doing psychedelics in a guided situation where someone has checked you out medically to make sure you’re sturdy enough to have the experience. But compared to other drugs I think the risks are remarkably slight, especially when you consider that there is no LD50 or lethal dose for LSD, yet the LD50 for Tylenol is a pretty small number of pills.

As a reputable journalist was it not legally self-incriminating to go out on a limb about your experiences?

Yes insofar as I am confessing to violating federal and state drug laws, but no in that it’s not a usable confession. I did have the book carefully lawyered, but honestly I was more concerned about protecting the guides I was profiling than in protecting myself. I was confident I hadn’t gotten myself into any kind of trouble. The risk to my reputation was probably greater but I teach at Harvard and Berkeley and haven’t gotten any shit from either institution—yet. [laughs] Knock on wood.

You were never drawn to the spiritual quest. Yet now in the psychedelic conversation you find yourself in the center of questions such as “What is consciousness?” What role did family religion play in your upbringing?

[laughs] Next to none! I was bar mitzvah’d against my will and that was the most religious thing I ever did. It was more of a marketing opportunity for my dad’s law firm and for my parents, who wanted to have a big party. I felt it was completely hypocritical. I was not a believer then and I’m not now. My point of view was that the laws of nature could explain everything and any claims to the contrary struck me as implausible. I tended to be a materialist though I have come to see the value of Jewish ritual and holidays.

A good grizzled empirical journalist?

[Laughs] Exactly! But my psychedelic experience shook that. And it wasn’t just my experience. I started out on this journey interviewing cancer patients, many of them terminal, who’d had profound, transformative spiritual experiences on psilocybin in drug trials at NYU and Hopkins. My talking to them raised all sorts of questions. Was what they were seeing true? Was their insight into the nature of ultimate reality something that could be confirmed? Was it plausible? That made me curious to try it. I realized I’d been a long time through life not thinking about it and that it was something to explore, even if I was skeptical. I thought I would learn something and maybe have a spiritual experience. Was that even possible? Because I don’t think I’d ever had one—except the warmth and good feeling of a shared meal or something, which I have described in spiritual terms.

I had the conception that spiritual experience was equivalent to a supernatural experience—that to believe in a spiritual realm was to believe in a world beyond the world that we can prove with our science and our senses. I was skeptical. I thought the opposite of the word material was supernatural.

What did your experiences reveal?

During my experiences that I describe in the book (and that I’ve thought about since as it’s become more vivid to me) is that spiritual experience is a powerful self-experience of connection. It’s a lowering of the walls that separate us from other people and nature. It’s an escape from the subject-object duality. We tend to think of ourselves as the only perceiving subjects, either us individually or us as a species. Everything else becomes an object. Of course when you believe that way it comes with the feeling that there’s nothing stopping you from doing what you do to the things you objectify—which is exploit them in one way or another—and not honor their own subjectivity or the fact that they have interests and agency and sovereignty.

What was so powerful to me was that as I experienced the dissolution of my go I felt a deeper connection to the people I was thinking about. And this deeper connection was particularly strong with regard to nature, which suddenly was just as conscious as I. So I came to understand that what stands between us and spiritual experience is the ego that builds walls and objectifies. What a wonderful thing that psychedelics could give a glimpse of a postegoic consciousness! It’s scary to lose your ego, obviously. But if you feel safe and willing to take the leap there are incredible treasures that lie on the other side.

Yay! And there’s a neuroscientific explanation about how the mind becomes quiescent with psychedelics.

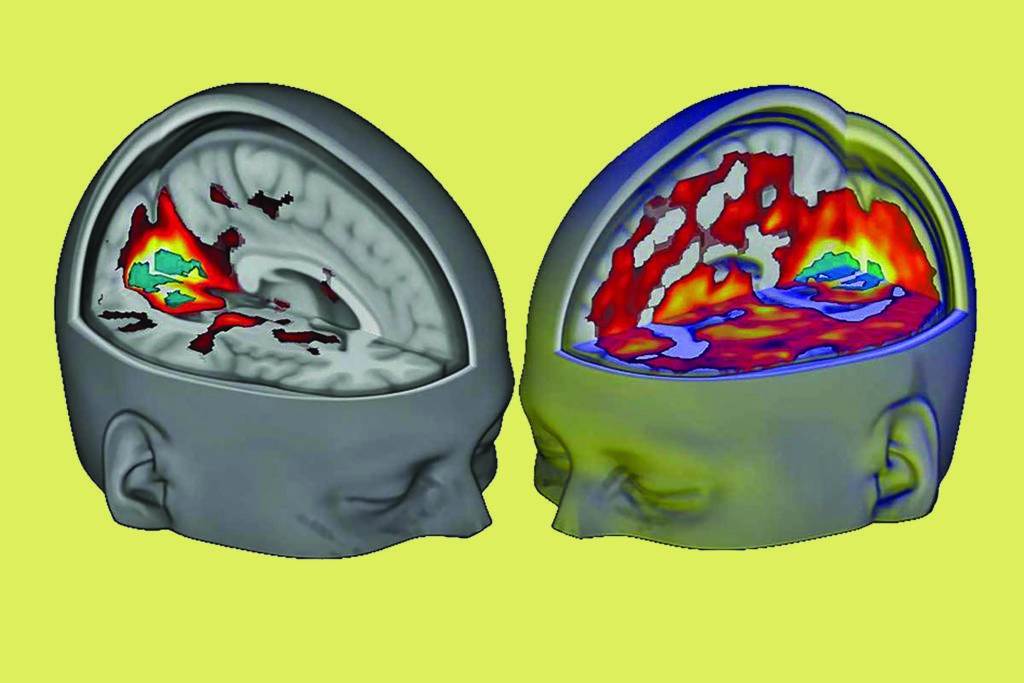

Yes, but it’s important to preface that we don’t really know very much about he mind or how it works. We have some clues but anything I tell you will probably look very different in ten years or five years. Or maybe next week! But a very interesting thing happens to the brain on psychedelics, at least by the measure of our imaging technologies, MRI [magnetic resonance imaging] and MEG [magnetoencephalography]. There is a part of the brain that is very closely identified with the self or the ego called the default mode network, and it goes quiet, gets quiescent as you said, with psychedelics.

The default mode network is a part of the brain that involves several tightly linked structures including the prefrontal cortex, the posterior cingulate cortex, and the limbic systems that are involved with memory and emotion. It’s a big communications hub in the brain that is involved with such things as self-reflection, time travel (which is very important to having a sense of self, being able to imagine yourself in the future or conjure memories from the past), theory of mind (the ability to put yourself in the shoes of others and impute consciousness to other beings, which is central to empathy and moral philosophy and things like that).

This is also where we go to worry and obsess and it’s where our mind goes when it’s wandering and not engaged by a task, or not engaged by the outside world. So it’s not an entirely happy place as it can get very self-reflexive. There’s evidence that depression is the result of an overactive default mode network, but psychedelics turns it off, or almost. When that happens some interesting things happen.

They’ve correlated the drop-off in blood flow and activity to the default mode network to a perception of ego dissolution. In other words if you’re feeling ego dissolution that’s how it looks in the MRI machine—these areas of the brain going quiet. So that’s one kind of proof that this is the home address of the ego to the extent that it has one.

They’ve done such tests on meditators.

When they scan the brains of very well experienced meditators, people with 10,000 hours of meditation, they put them in an MRI and they too have a dramatic drop-off in default mode network activity. I’ll bet if you could measure other experiences that provide a sense of flow or a strong connection with others or nature that you’d see something very similar. I think it’s interesting that the loss of self, which of course is a goal of meditation, has these benefits.

The other thing that happens when the default mode network goes offline is that interesting things happen in other parts of the brain. Since it is the communications hub lots of signals pass through it. When it goes offline, parts of the brain that don’t ordinarily communicate with one another begin to. They strike up what’s called “cross talk.” So you will get a situation where the visual cortex is speaking directly to your memory or your emotion centers. You’ll start seeing things that you’re wishing or fearing.

Isn’t there a name for that?

Hallucination.

What is synesthesia?

Synesthesia is the cross-firing of different senses, so you can suddenly see a musical note or smell a note, or hear the sound of a certain smell. That too may be a result of taking the default mode network offline and letting networks involved with visual perception talk to networks involved with audio perception. I had a very strong experience of sound creating a landscape where every note represented a thing, a palpable thing in that landscape. One of the more interesting phenomena of psychedelic experience is synesthesia. Some people have it naturally but most of us don’t. And psychedelics kind of reliably will do that.

With psychedelics it seems one can hack “into the Garden” so to speak. But eventually the effects wear off and one is bounced out. We can’t live on psychedelics to maintain that state.

After I had my most profound psychedelic experience, the one I describe in the book where I experienced the dissolution of my ego and the sense of complete merging with a piece of music, in the integration after I asked my guide, who I call Mary, “So I’ve had this big experience. I realize the ego is not the be all and end all, that you survive the death of your ego and it can be quite wonderful, but what do I do with that? What good is it? My ego is back in uniform, on patrol, up to its old tricks.” And she said, “You’ve had a taste of something and that something is quite profound and you can cultivate it.” And I said, “How?” And she said, “Through meditation.” For many people meditation is the way that you convert whatever the fruits of psychedelic experience are into an everyday practice, because you’re right, you can’t take psychedelics every day. Nobody would want to. It would be counterproductive.

But it’s no accident that all of the important American Buddhists of the Baby Boomer generation who brought Buddhism to America such as Jack Kornfield, Joan Halifax, Jon KabatZinn, all had important psychedelic experiences which they will talk about now. Their thinking was “How do you bring this into your life?”

My experience was that the psychedelic experience made me a better meditator. I had a sense of the destination I was trying to get to. It’s always easier to get back to a place than to get there for the first time. So I found it very useful to the extent that I am cultivating that post-egoic vision—mostly not successfully. But that’s the place where I work on that stuff.

[Laughs] So you’ve evolved from the grizzled empiricist to a New Age spiritual dude?

[Laughs] No, I wouldn’t go that far because my understanding of spirituality is pretty secular. It doesn’t require any kind of supernatural belief or faith. I’ve met so many people in this community who are convinced that there is a transpersonal dimension to consciousness. I get where that comes from and you certainly have that feeling on psychedelics, but I’m loathe to assert that the kind of insights you have on psychedelics about ultimate reality are necessarily true. They might be. Maybe we should take them seriously but I’m not sure quite how seriously to take them.

My understanding of spirituality is pretty consistent with Western psychology—that connection is really the key. And connection happens when you let down your guard, which is to say when you take your ego offline to the extent you can shrink it. And many things do this. The experience of “awe” has that effect too. You can understand this strictly in psychological terms without having to use spiritual vocabulary. I think the spiritual vocabulary is good at suggesting just how special and meaningful those moments are, or “sacred,” as spiritual people say.

Subsequently have you been drawn to spiritual philosophy or dipped into the texts?

When I was writing the book I did. I got interested in Buddhist and Hindu thinking about the mind, which is a pretty coherent systemic examination of consciousness. It’s as good as anything we’ve come up with. So I did look at that, usually in secondary sources. I was curious to read about consciousness. Where does it come from? How is it generated? Is it generated? Might it lie outside?

The wisdom of the sages is that everything is consciousness and ego separates us from That.

And that mind precedes matter, too. I mean we assume it’s the other way around. That’s the flip. The flip is seeing that “Oh my God, these are all manifestations of mind—all this material world stuff.” So for me to have gone from thinking that was ridiculous to having an open mind is to have made an awful long journey. But I’m not all the way there yet. I’m still chewing on it. I also wonder if there are ways to know this for sure.

You could trust. Or have a near-death experience.

Not eager for that. I’m still enamored of the scientific method of testing propositions, and I don’t know how you test this one.

I’ve long been spiritually curious. It’s been long path of identifying and confronting my thoughts, mind, ego—never easy.

It’s a challenging path because the landmarks along the way can be confusing and maybe the method that works for living in the material world doesn’t work in that world. I’m a very novice explorer of these territories, having only had these brief glimpses.

I think spiritual people are happy to share. It’s like “Yay, come on board.”

[Laughs] Oh, I know, people are very welcoming! I haven’t gotten the reaction of “Oh, newbie.” That’s also been true with people with a lot more psychedelic experience.

What is your opinion about microdosing, which has become very popular? I see it as a kind of crutch for keeping the lights on and for staying in the zone.

I don’t know that microdosing has any particular spiritual implication. It doesn’t seem to be how people are using it. They’re using it for healing and to get a little productivity boost at work, neither of which sound like particularly spiritual endeavors. I didn’t write much about microdosing because we don’t know very much about microdosing. We have the anecdotal reports now of several thousand people that Jim Fadiman has collected and it’s a very interesting data set. But it’s uncontrolled and there have been few if any controlled trials of microdosing to indicate whether something real is happening or whether this is a placebo effect. Not to discount the very powerful placebo effect!

It wouldn’t be surprising that a psychedelic, even in a small dose, would prepare the mind for some significant change, because of what psychedelics represent to us. But rigorously controlled double-blind trials might ruin this

very good placebo. I think the jury is out but without doubt there are people who find it useful. But it’s not about shrinking the ego. It’s about a kind of brain vitamin. I have talked to people who feel it’s helped with their depression or anxiety and others who feel it’s helped with their creativity.

You seem to be a genuinely happy person. Is that a fair assessment?

I think you’re born with a certain temperament. I am a glass half-full kind of guy. I know because I’m married to someone who’s otherwise. If you’re in long-term relationship you tend to push each other to your corners of personality. It’s the luck of the draw. I don’t see myself as having had an outrageously happy childhood or anything, but I generally have a positive outlook. I keep telling people, “Don’t worry, Trump won’t even be on the ballot in 2020.” I’m starting to realize I’m going to be wrong. I warn people not to take my political prognostication with too much seriousness.

Where did you grow up? What did your daddy do and that kind of stuff?

I grew up in the suburbs of New York, first on the South Shore of Long Island, then on the North Shore. We moved when I was six. Both were suburbs. One was a lower-middle-class tract house. Then when my parents were doing a little better we moved into a prettier, leafier suburb called Woodbury with curving roads rather than a grid. I went to public school and was very attracted to nature. I spent a lot of time in the woods and had a vegetable garden when I was eight. I always liked to grow food. I didn’t call it a garden. I called it a farm because it was a going concern. When I could grow a couple strawberries I put them in a Dixie cup and sold them to my mom.

It wasn’t all sweetness and light. My dad was an alcoholic. He’s dead now so I can say that. Watching him get sober, which didn’t happen until he was in his 40s, was an amazing lesson in the power of self-transformation. He just did it. I saw him reinvent himself several times. That was a great model to me—that you can hit bottom and rebuild your life. He also reinvented himself professionally. He was a lawyer and then a corporate guy. He had a small business investment company and then became a teacher. Then he became a writer and then a consultant. He ended up having a powerful impact on many people as their consultant. He became a kind of guru to a lot of people. I still run into people who say, “Your dad changed my life.” So transformation, which obviously is the title of this book, is a subject very dear to me. That’s been part of my attraction to gardening—watching transformation up close.

Mom?

My mom was a very creative person and a writer. She’s still alive. She was training to become a teacher when I was a teenager. She had four kids. I was the oldest. She wanted to go back to work so she got a degree so she could teach. But there were no jobs so she ended up working at New York magazine. First she got a job as a secretary and then became the editor of Best Bets, which was a very popular shopping column. She’s since written cookbooks and a shopping guide to New York. She was the more literary of the two, the big reader. My dad was not a big reader except for thrillers. She went to Bennington College, where I also went, and was a literature major. We shared that love of books.

Your father died recently. How did that play out for you?

He died in January of 2018. He’d been sick for a while with cancer. First he had esophageal cancer, which he actually beat. Then he had lung cancer. He’d been a smoker for a long time. What can I say? It was horrible. One of the reasons I wrote this book, I realized in retrospect, was because I was very curious about death and how one processes the prospect of dying. I started this quest on psychedelics talking to people who had cancer diagnoses. One of the reasons I wanted to talk to them was because I really couldn’t talk to my dad about this. He processed his diagnosis very internally, by often putting it out of his mind entirely. Having a conversation about death or mortality was not something he wanted to do or was capable of doing.

So here was this cohort of people, these patients who had had this psychedelic experience that left them dying to talk about it. They were so engaged by what they’d seen that they had this incredibly open, candid, lucid way of talking about death because they had glimpsed it. They had rehearsed it and in a way had a near-death experience. That satisfied a lot of my curiosity about the conversation I couldn’t have with my dad. I think the amount of time I spent with people who had cancer equipped me in some ways to be with him for the end, and to my surprise I was able to be very present, both figuratively and literally, at the end.

I spent the last eight days or so living with him in his apartment doing my best to take care of him, make him comfortable. He died at home. I wasn’t the only one. My sisters were very present too and several of his grandchildren. He literally died surrounded by his family. These things are never beautiful but it was better than it could’ve been. Was he peaceful at the end? No. I don’t think he was. Was he ready to go? I’m not sure. There’s so much I don’t know. I know much more about the deaths of these strangers than I do about him.

Didn’t your wife credit psychedelics as having helped you become more patient and present with your dad?

Because people like you were asking, “How did psychedelics change you?” I was asking my wife the question as I was trying to find a way to illustrate or quantify that—because it’s kind of subtle. It’s not like, “I was that way and now I’m this way.” She offered that example and I think she was right—that I was much more open and present with my father’s death. I’m a very busy person and could’ve manufactured reasons I couldn’t be there every day at the end. But I wanted to be there. I wanted to be available to him. I wanted to understand the process as best I could. So I may have psychedelics to thank for that. One of the domains of personality that changed was in the direction of greater openness.

You mentioned your dad’s alcoholism. Was he part of the 12-step program?

He got sober on AA, was religious about going, and worked the program well. We had all celebrated the annual anniversaries of his sobriety since the late ‘70s. He very much believed in a higher power and became a spiritual person. He basically converted the philosophy of AA into his business philosophy and his how-tolive philosophy, and had a very successful consultancy that sold people the wisdom of AA although they never knew it. “One day at a time.” “It gets better.” “Your problem is between your ears.” All these things he got from AA.

You document that AA had a psychedelic inception.

There’s some interesting crossovers. The cofounder, Bill W., had already gotten sober on a psychedelic called belladonna at a hospital in New York in the ’30s. Later in the ’50s in LA he received LSD therapy and became convinced that this medicine could help people quit drinking. In the ’50s the theory was that the LSD trip was like the DT’s, delirium tremens, that it gave the same conversion experience that drunks got who hit bottom. He thought it should be part of the fellowship and brought it to the AA board but they felt that it would be a controversial and confusing message given that they believed in swearing off all intoxicants. They rejected his proposal.

I used to go to meetings with my dad just to keep him company because he wanted me to see what was going on. I thought the spirituality of AA, the higher power and the emphasis on community were to dilute and hide its Christian identity so as to be as open as possible. But they were not actually. Their view of spirituality was like the psychedelic view of spirituality—that faith in a higher power was part of an effort to transcend ego—that ego consciousness is what gets you in trouble with substances like alcohol. To the extent you could disclaim responsibility for what happens day to day and realize that there is a higher power involved, you could lighten the load of your ego. At least that’s how I understand it.

Psychedelic therapy in the ’50s and the way AA developed its methods also shared a similar kind of spirituality emphasizing connection. You go there to get connected to other people. Until you’re connected you’re not going to be able to break your addiction. You’re sustained by these connections because you don’t want to let people down. They’re there to help you if you slip. There’s a turning both toward a higher power on the vertical axis and toward community on the horizontal axis.

How were you drawn to becoming a journalist?

I was an English major, always interested in writing and publishing. I was involved in a literary magazine beginning in junior high school and was on the newspaper in high school. I was the movie critic and the food critic, basically so I could have free dates in New York City. I just loved ink. In high school I worked for the Vineyard Gazette on Martha’s Vineyard and for the Paris Review in college. Then I was an intern at The Village Voice, then got a paying job there. I didn’t think I could make a living as a writer so editing was the next best thing. I worked as a magazine editor at a succession of magazines that flopped, leading to one that manages to survive, Harper’s. I worked there for ten years as an editor and began writing in a serious way with my first book, Second Nature.

I wrote on weekends and in the evenings, and started my second book there, A Place of My Own. Halfway through I realized I had started it all wrong and had to go back to the beginning. We had just had our son Isaac and the idea of writing on weekends and evenings no longer had any appeal. I reached a fork in the road where I had to decide—did I want to stay at Harper’s as a magazine editor or was I willing to take the leap and become a full-time writer? It was a very important fork in the road. I decided to become a writer.

We left New York to live in rural Connecticut where we could live more cheaply and send our kid to public school. I finished my second book and launched my third [The Botany of Desire] and that’s when I made a living as a writer.

You were worried about financial success?

My wife was a painter. Usually when you’re married to a writer or a painter, one has a real job with benefits, but neither of us did. So it was a stretch for a long time.

[Laughs] I can’t calculate the numbers but you’ve sold a lot of books, my friend.

I have, actually. I have been so lucky because I’m no better than so many writers but I’ve caught a couple cultural waves. Usually you’re lucky to catch one and I’ve caught two pretty big ones. I feel fortunate and that’s one reason I teach writing—to hopefully share with others.

How is journalism a creative process?

On a couple levels. The most important is figuring out how to organize material and tell a story. Life doesn’t automatically resolve itself into narrative—it has to be coaxed. A lot of the creativity is figuring out “Where is the story?” “Where do you start?” “Who’s the hero?” “How does it end up?” The old problem of framing nonlinear beginnings, middles, and ends. How to find the laundry line that knits a story together and that you can hang your exposition on. I see writing as taking this three- or four-dimensional reality and passing it through the needle of a narrative, one word or one sentence after another.

Then there’s the creative skills that go into connecting with people so they tell you things they probably shouldn’t—interviewing. Or keeping someone longer than planned. [laughs] I compliment your creativity!

Oh gosh! Thank you. Is there something specifically “Michael Pollan” about your approach to teaching journalism?

I don’t know if it’s specifically “Michael Pollan” as I’ve never taken a writing course and don’t really know how others teach. I learned to write as an editor at Harper’s. The way I teach is getting people to write and then I edit what they do. It’s incredibly time consuming. I wish there were a better formula because I don’t enjoy it. But there’s tremendous value to actually seeing how someone takes a sentence that is written in the passive voice and turns it around to an active voice. You can put that on a blackboard all you want but unless they’ve actually seen you perform that jujitsu it’s never going to stick. I do close editing on my students’ work. I talk about structure and how any piece has an x-axis and a y-axis and needs that laundry line to pull people through. The most common statement in office hours is “I can’t find a laundry line.”

At 15 I learned a lifelong lesson about discipline and keeping a clear head for writing. During summer school I would smoke weed, listen to the Grateful Dead, and write. Of course I thought my stuff was great but the next day it turned out to be inchoate crap. What’s your experience with mind-altering substances and the creative process?

Coffee and tea are important to my creative process—great aids to focus. Psychedelics are the opposite. As I described, that needle eye that you’re passing the thread of narrative through—forget it. Psychedelics are not going to help you. Caffeine is good for narrowing focus whereas psychedelics draw you to all those other things that you’re ignoring. Alcohol as never had anything to do with my writing though it’s a way to unwind after you’ve written. Pot—never.

What are some of your next projects? Is being a food journalist still in your bag of tricks?

I’m writing about something right at the intersection of food and drugs and that’s caffeine. I’m doing a long article about caffeine because I’m interested in it. It’s one of the cleverest drugs ever invented by a plant for the manipulation of animals.

I’m profoundly not a fan. I believe if you want more energy—drop caffeine.

What’s the problem with caffeine? You think it takes as much energy as it gives, or it takes more?

Yes. The recognition came a long time ago in the ’80s after doing cocaine all night, grinding my teeth as the birds were waking up. I had this flash about those old ads that said “Speed Kills.” Basically you can whip the horse and it will jolt—but you’re pulling from somewhere.

That’s a very Emersonian take—that there’s a compensation. That might be true but it’s a very old American idea and one of the questions I am trying to answer. Is it a free lunch? So you don’t use caffeine? Is there another stimulant?

I don’t [laughs]—a journalist who doesn’t use caffeine! I guess I meditate as a way to keep it in control.

I’m going to go cold turkey as part of this to explore some of those issues but keep putting it off. I don’t know why.

[Laughs] Because you’re hooked.

[Laughs] I’m totally hooked. I agree. But I think an addiction where you can get what you’re addicted to and you have an expectation of a continuous supply—is that such a bad thing? I don’t know.

Any general particular likes or dislikes you care to mention in closing?

Too many to enumerate. The current political moment is the top of the list. I’m worried for our country in a way I never have been before. I didn’t worry through the ’60s, as crazy as it got when I was waking up to news of the assassinations of my heroes like Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy. I had a sense we were still moving in the right direction despite the craziness. I don’t feel that way now.

Journalism is under attack. What’s your assessment about journalism today?

Journalism has never been more indispensable and never been more precarious at the same time. There’s a tremendous audience for journalism but there’s no longer a reliable business model. That seldom happens, right? Normally if there’s an audience for something somebody figures out how to pay for it. The New York Times is figuring it out. A few places are figuring it out. It’s really hard, especially at the level of local journalism. I worry about that. It’s no accident that the collapse of local journalism is accompanied by the rise of a politics of ignorance—not to mention corruption. You need journalism to keep tabs on things. I worry about what’s happening at the state level—state government—where the scrutiny of that powerful local paper in a state capitol is gone in so many places. We’re going to pay the price for having weakened journalism. The companies that weakened it, like Facebook and Google—they’ll pay a price too. They didn’t mean to but essentially they’ve hollowed out journalism. It’s absolutely the wrong time to be weakening journalism.

A final message to readers, many whom are your fans?

Thank you. Thank you for reading me. It means a lot that people still read books. Thank you for reading anything, not just me. Thanks for reading magazines. Thanks for reading print. Thanks for supporting writers.

Rob Sidon is publisher and editor-in-chief of Common Ground.